Horley is a home counties commuter town beside London Gatwick airport (LGW) and situated halfway along the London to Brighton railway line.

Horley Town

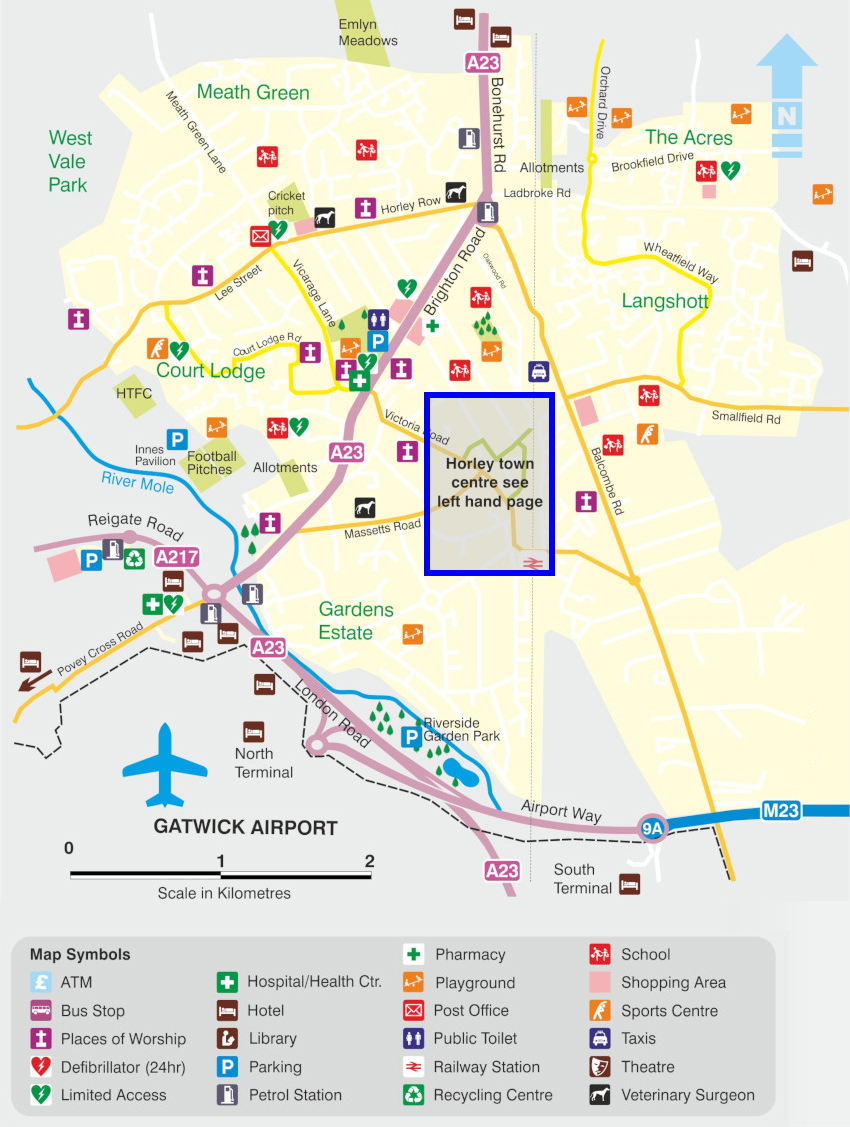

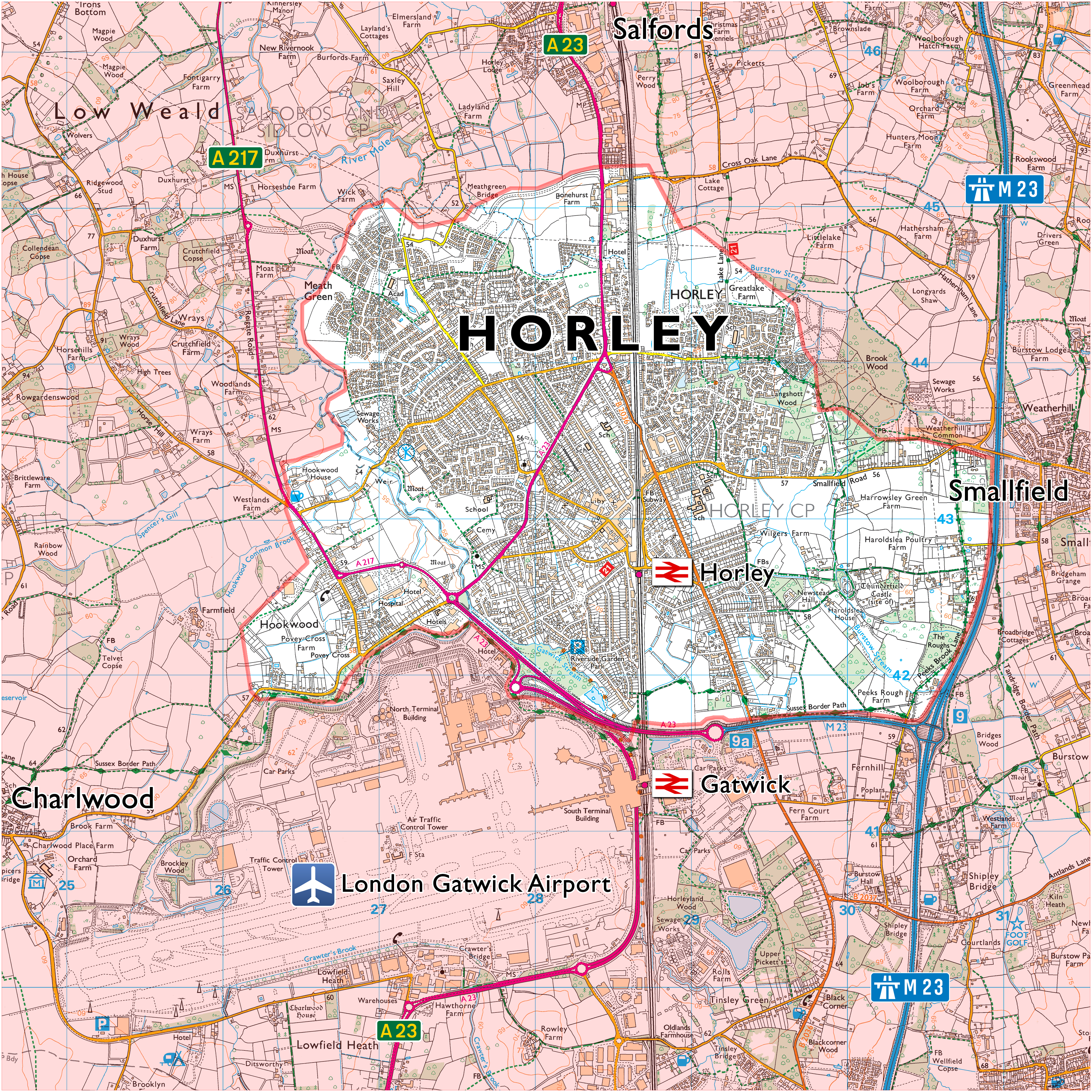

On the map

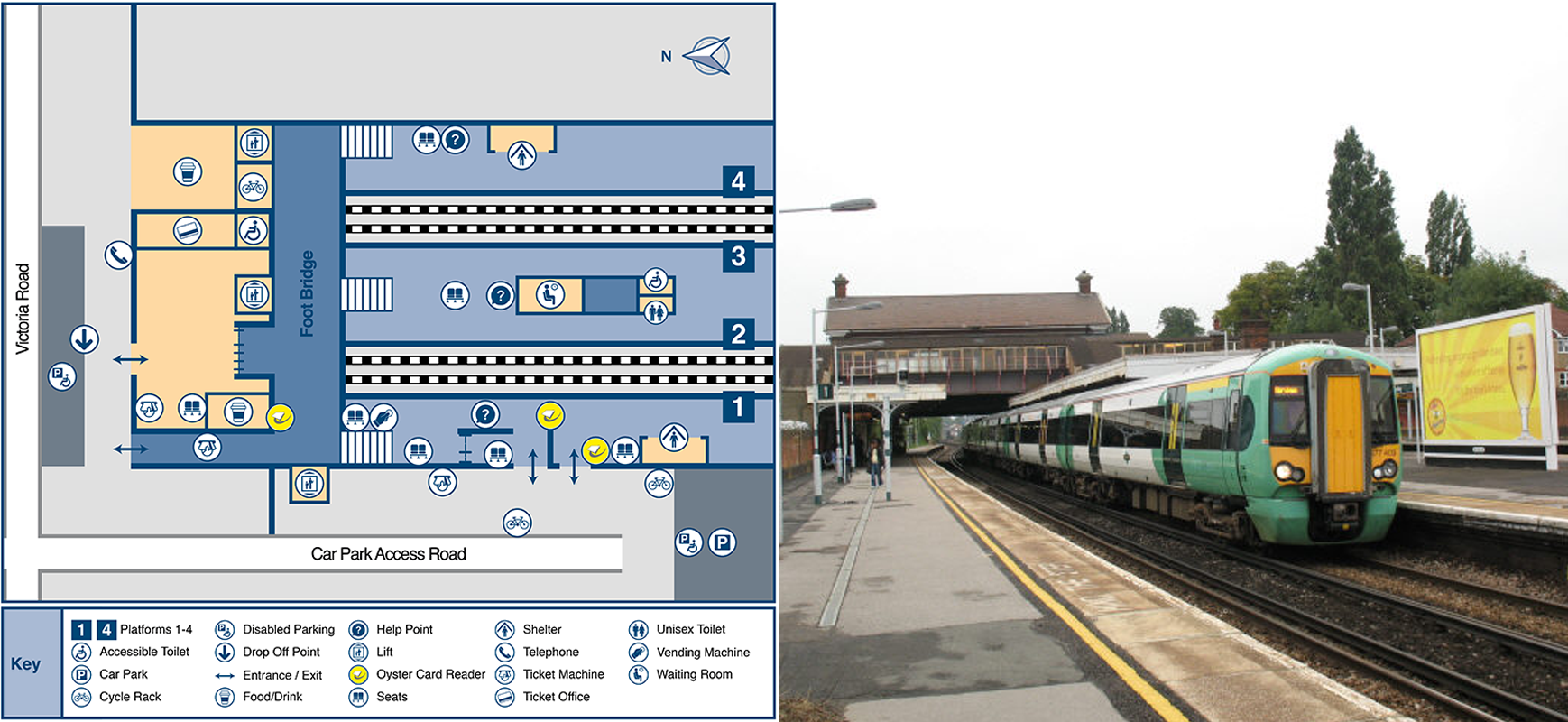

London–Brighton main line

Direct trains also depart from Horley travelling to London St Pancras International, home of the Eurostar and thus, high speed connections to Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and Disneyland.

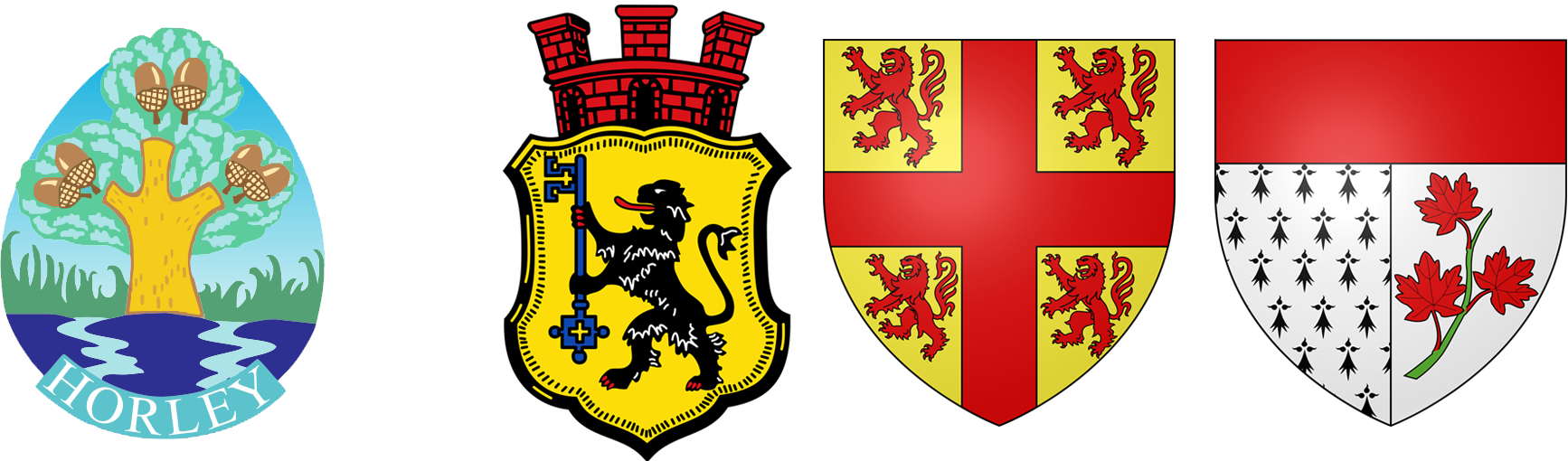

Horley homages

An addman [sic.]

Located midway between London and Brighton, Horley lies south of the twin towns of Reigate and Redhill and beside Gatwick Airport. The mainline station provides a regular train service to London and Brighton. There is easy access to the M23 and the town is also linked to Crawley via the Fastway bus service. A shopping centre, post office, library, variety of restaurants, leisure centre and recreation grounds can all be found within the local area. Nursery, primary and secondary schools are located across the town.

Another addman [sic.]

Horley is a small town with big connections. It is halfway between London and Brighton, and ticks the boxes for planes, trains and automobiles with Gatwick Airport, the M23 and the M25 right on hand, and direct trains into London taking less than an hour. With these credentials, it has become a popular residential base for commuters and has a strong community feel and plenty of excellent local amenities.

Page contents:

- Horley by area →

- Horley, a history →

- Horley, its name &c. →

- Horley in pictures →

- Horley, Gatwick & Controversies →

- Horley, Maps & Cartography →

Horley by area

Although Horley does not have named-on-road-sign neighbourhoods—like Crawley does—the following areas are commonly referred to:

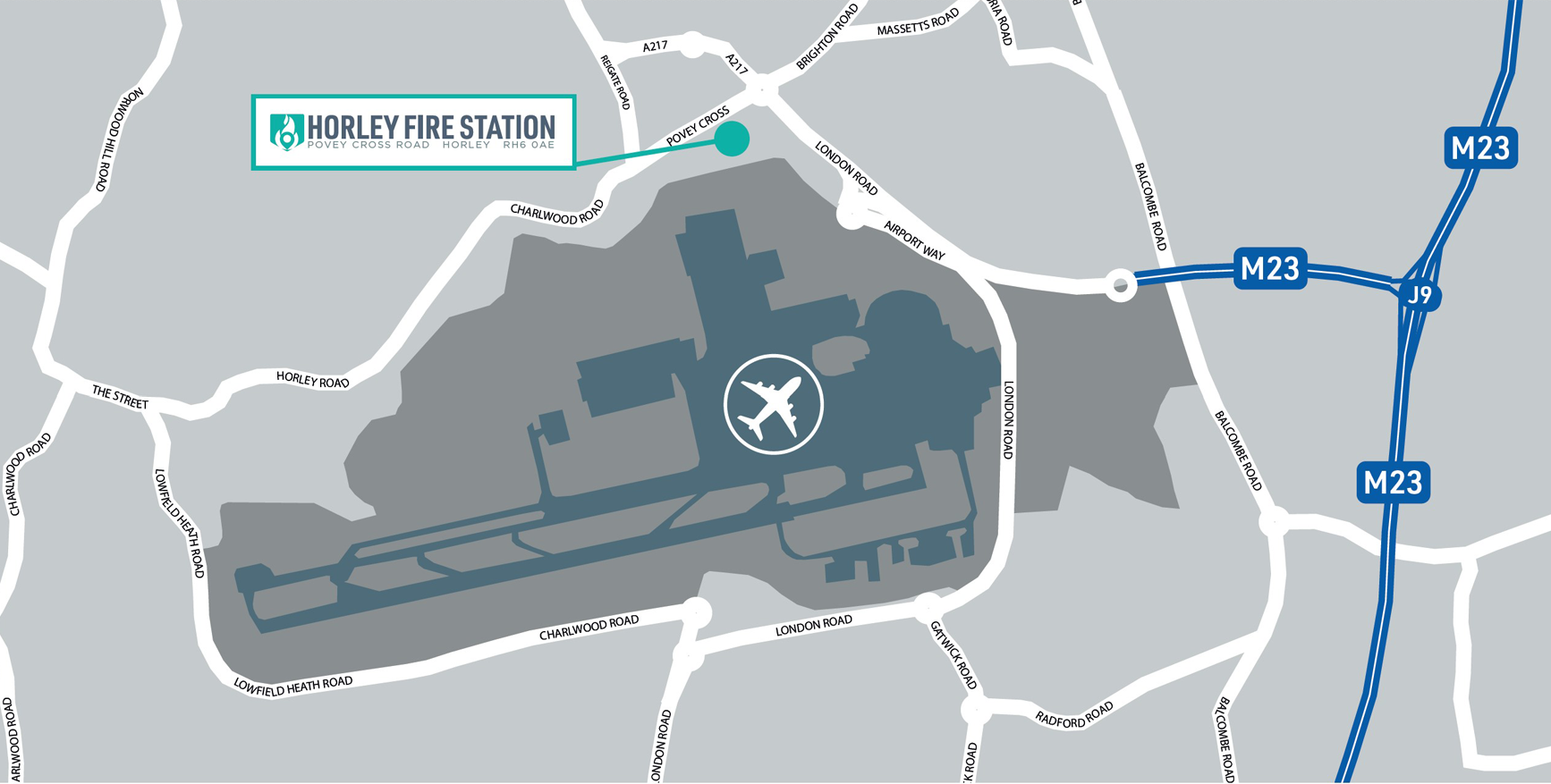

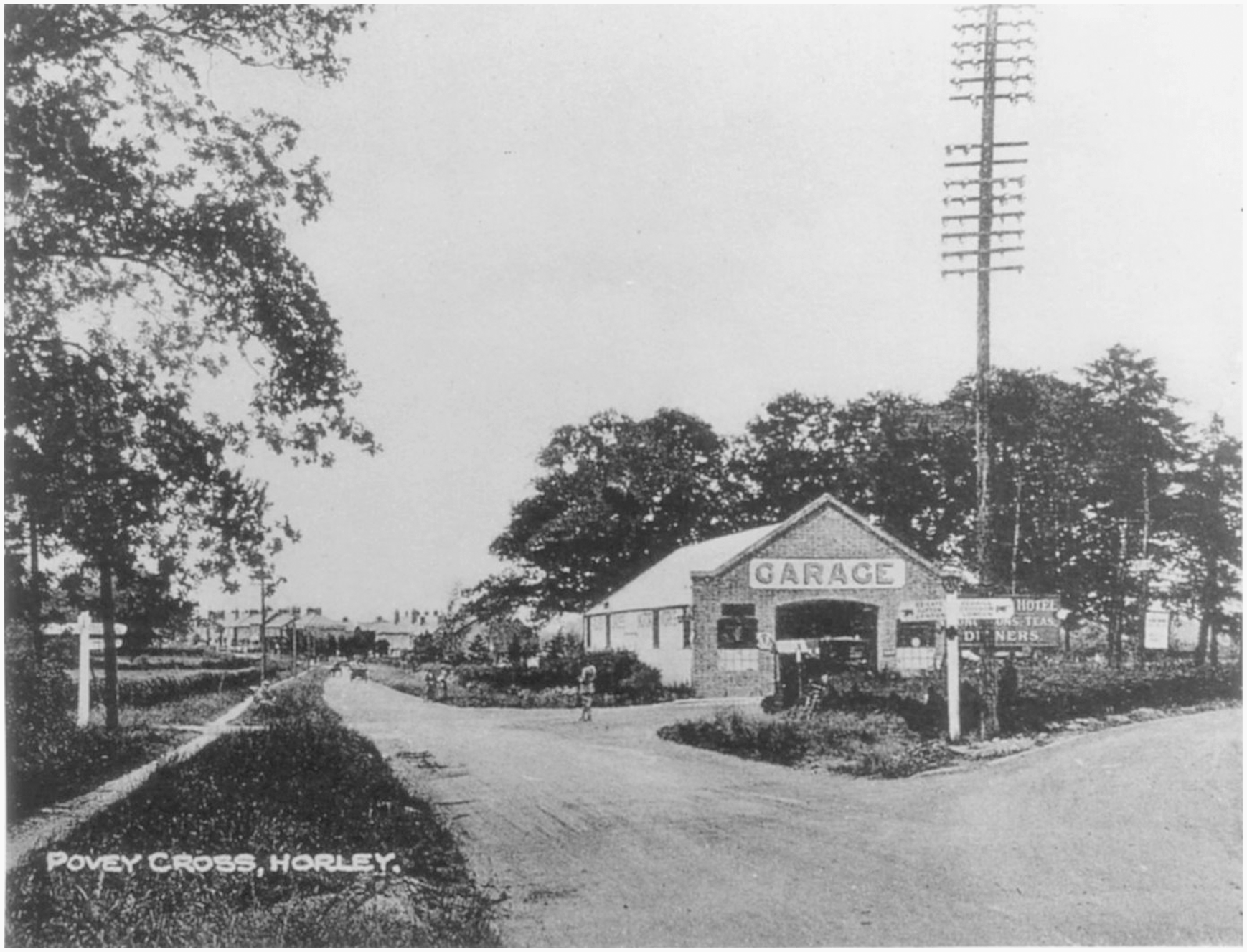

01. Hookwood/Povey Cross

Hookwood/Povey Cross →

Hookwood and Povey Cross are on the western outskirts of Horley. Many international hotels are situated here as is Tesco Hookwood. Several large housing developments are planned here. Hookwood and Povey Cross are directly beside the airport.

02. Gardens Estate

Gardens Estate →

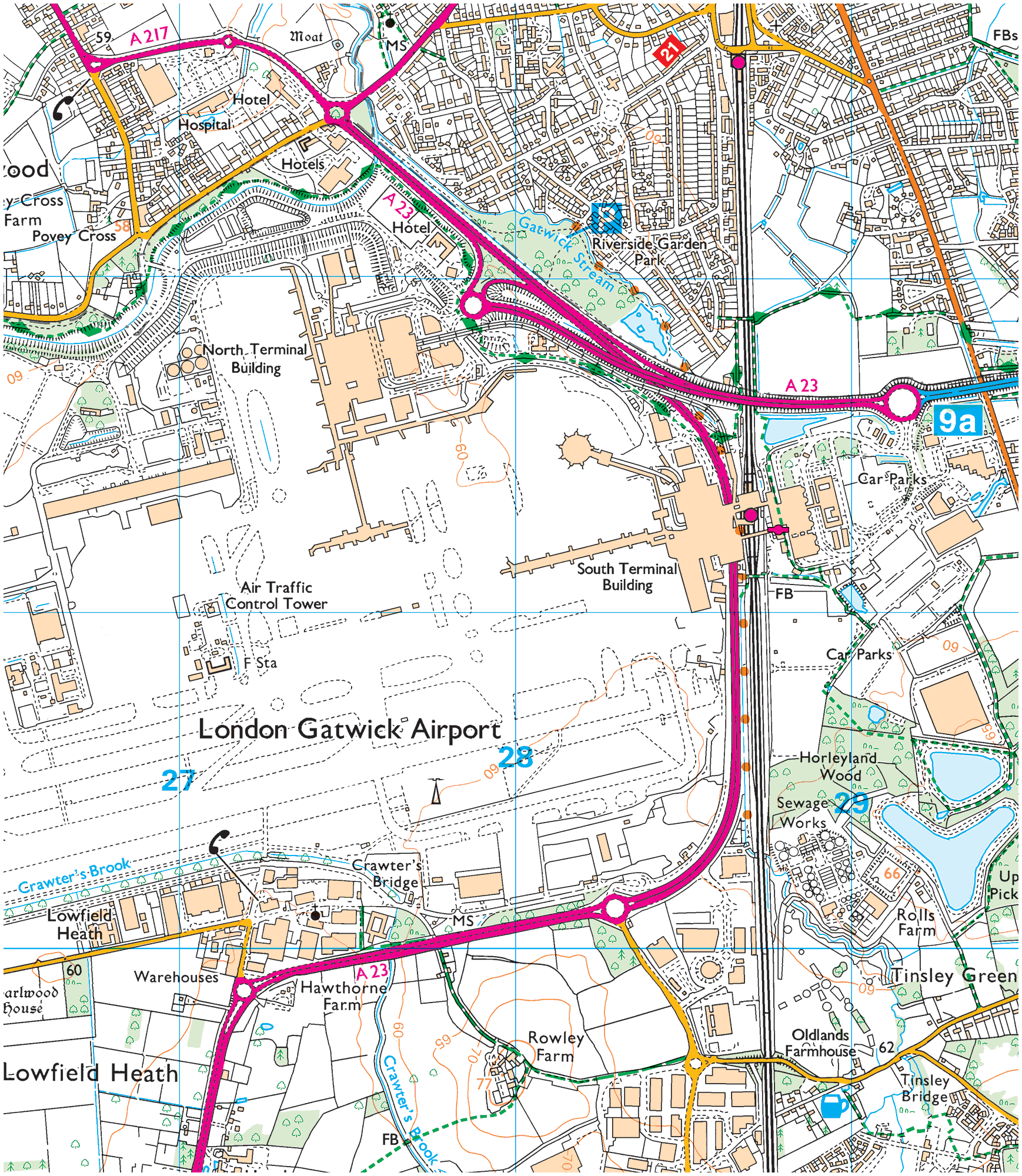

Gardens Estate is very close to Gatwick airport and those working at LGW can easily access the terminal building via footpaths from the recreational area, Riverside Garden Park via the underpass of Gatwick airport station.

03. Haroldslea

Haroldslea →

This area comprises: The Balcombe Road (B2036) and the roads leading from it between Oakwood School and the A23/M23 link road flyover. For example, Limes Avenue which was originally laid out in 1936 and still retains some of the Lime trees planted at that time.

04. Court Lodge

Court Lodge →

This neighbourhood was set out in the 1950s and 1960s. It has a mixture of flats and houses. It is home to Horley leisure centre, several airport hotels and a couple of places of worship.

05. Horley Central

Horley Central →

This area includes the town centre which has quite a lot of purpose built residential flats and roads such as Church Road, Massetts Road, Pine Gardens, Ringley Avenue and, Russells Crescent.

06. Langshott

Langshott →

This area of Horley stretches eastward towards Smallfield. Immediately to its north is the new estate called The Acres. This area is home to Langshott Manor, which was built in 1580; it is now a luxury hotel.

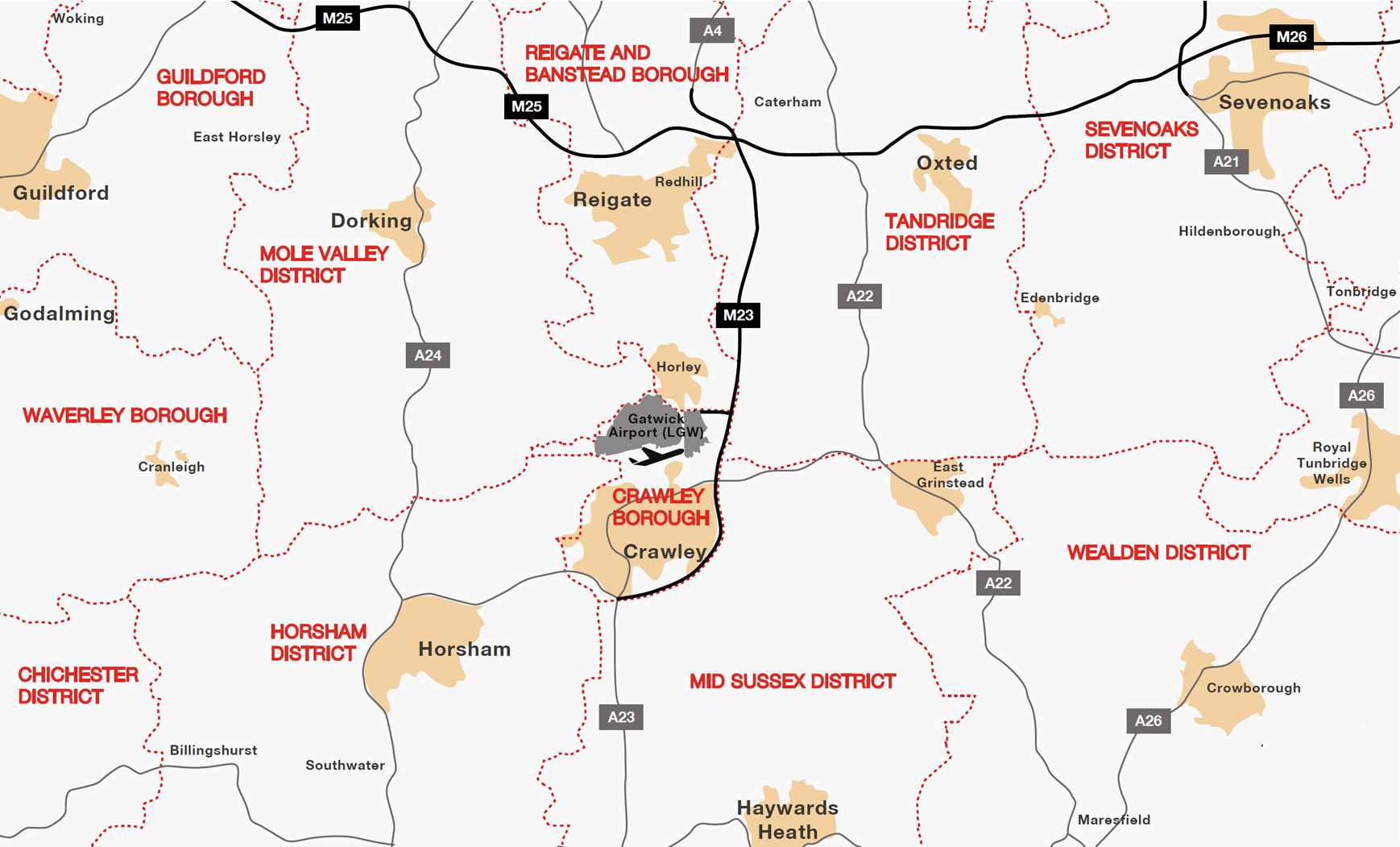

07. Meath Green

Meath Green →

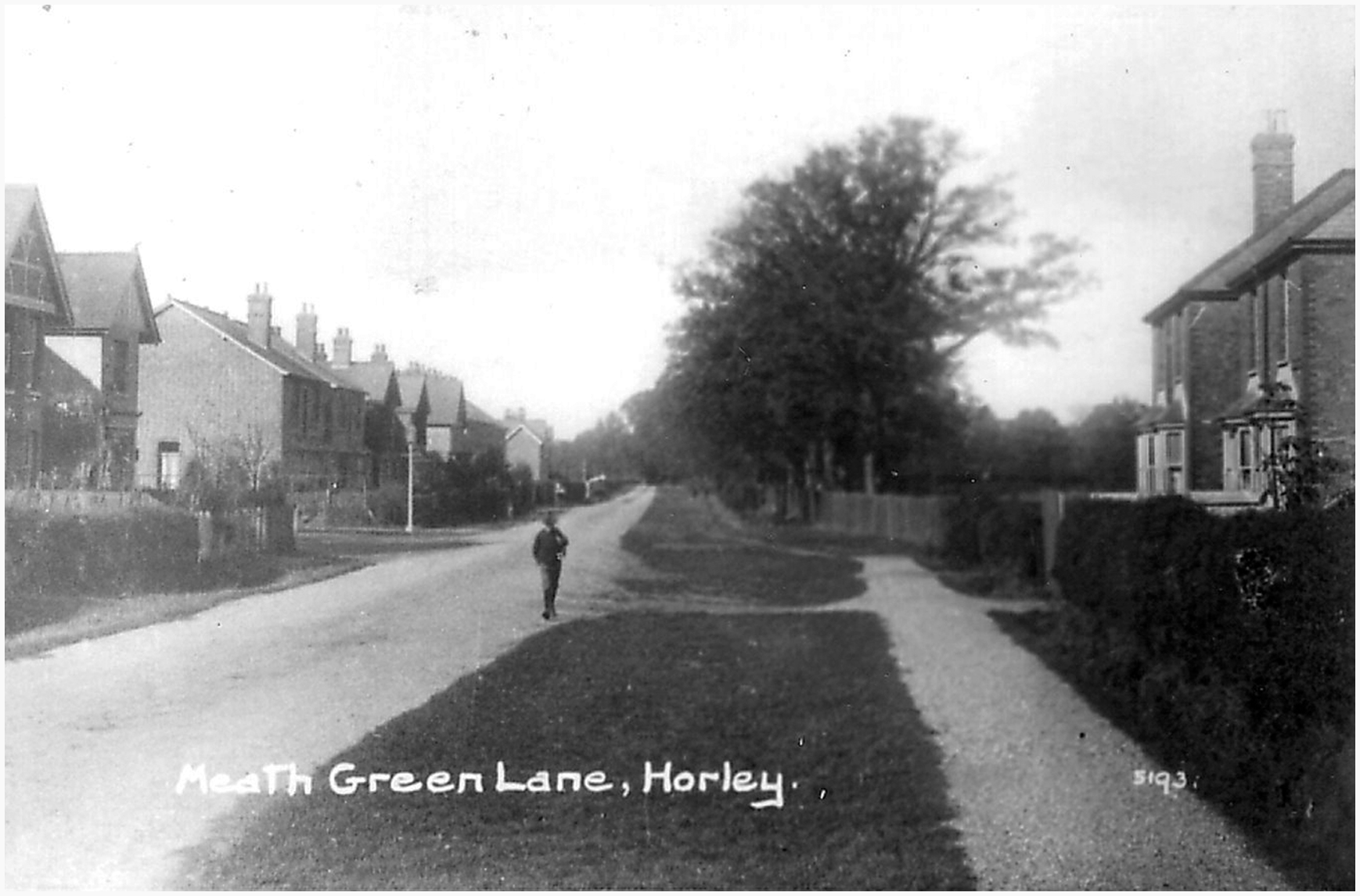

Once upon a time this area was called Moy Grene, and it has some of Horley’s oldest homes. Today, the vast majority of the homes in this area where built from the late 1950s onwards.

08. The Acres

The Acres →

This new neighbourhood of over 700 homes is in the north east of Horley and Langshott. The development was built mostly by Barratt and Bovis Homes between 2010 and 2016.

09. West Vale Park

West Vale Park →

This new neighbourhood is to the north west of Horley and joins onto Meath Green. To date, around 1,600 new homes have been constructed:

• Crest Nicholson brochure →

• Fabrica brochure →

• Taylor Wimpey brochure →

10. Gatwick

Explore Gatwick→

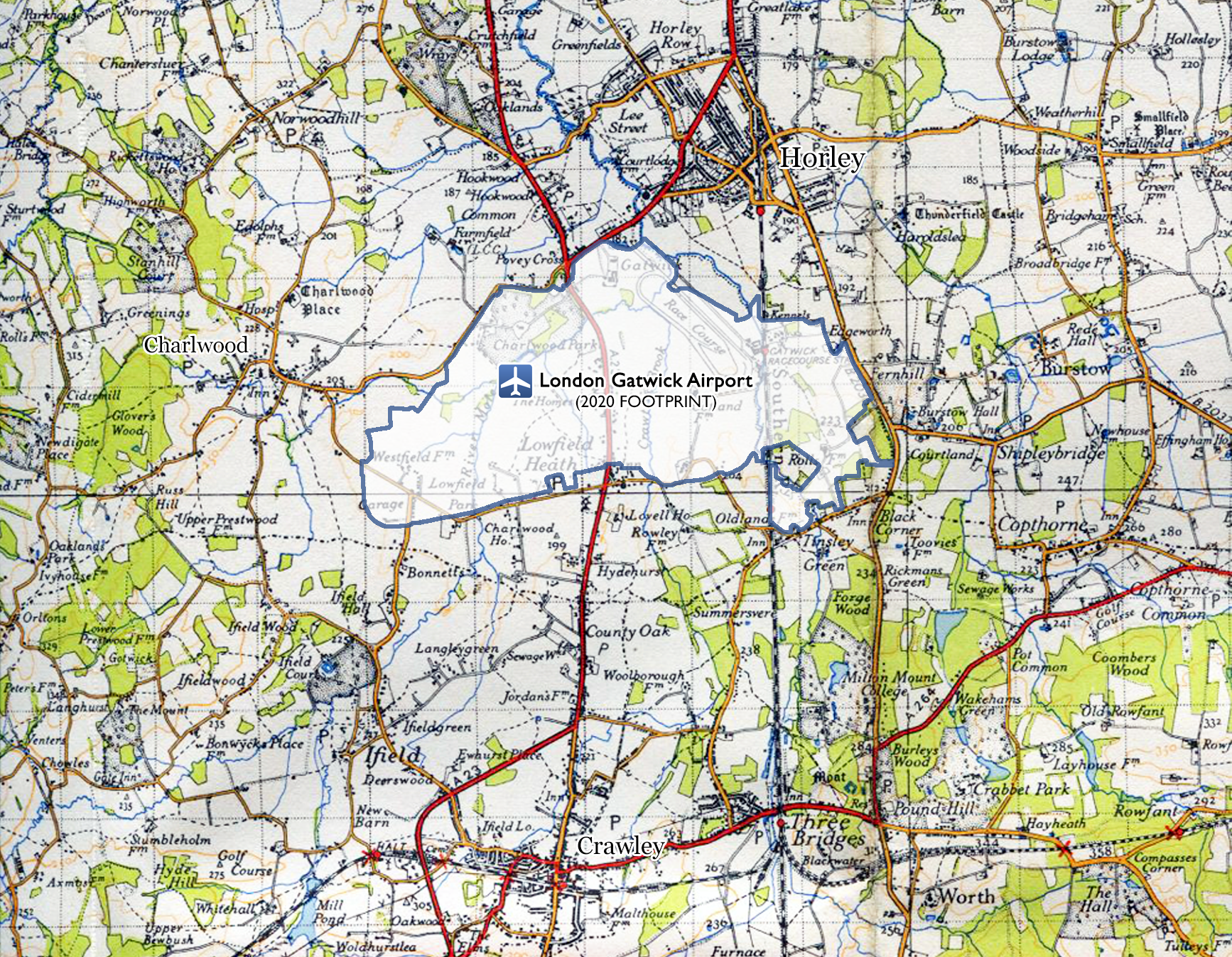

Gatwick airport is included as an area of Horley because historically it was part of Horley and, it remains adjacent to this day. Gatwick, before becoming a major international airport, was a famous horse racetrack which hosted the Grand National on several occasions.

Horley neighbourhoods

01. Hookwood/Povey Cross

02. Gardens Estate

03. Haroldslea

04. Court Lodge

05. Horley Central

06. Langshott

07. Meath Green

08. The Acres

09. West Vale Park

10. Gatwick

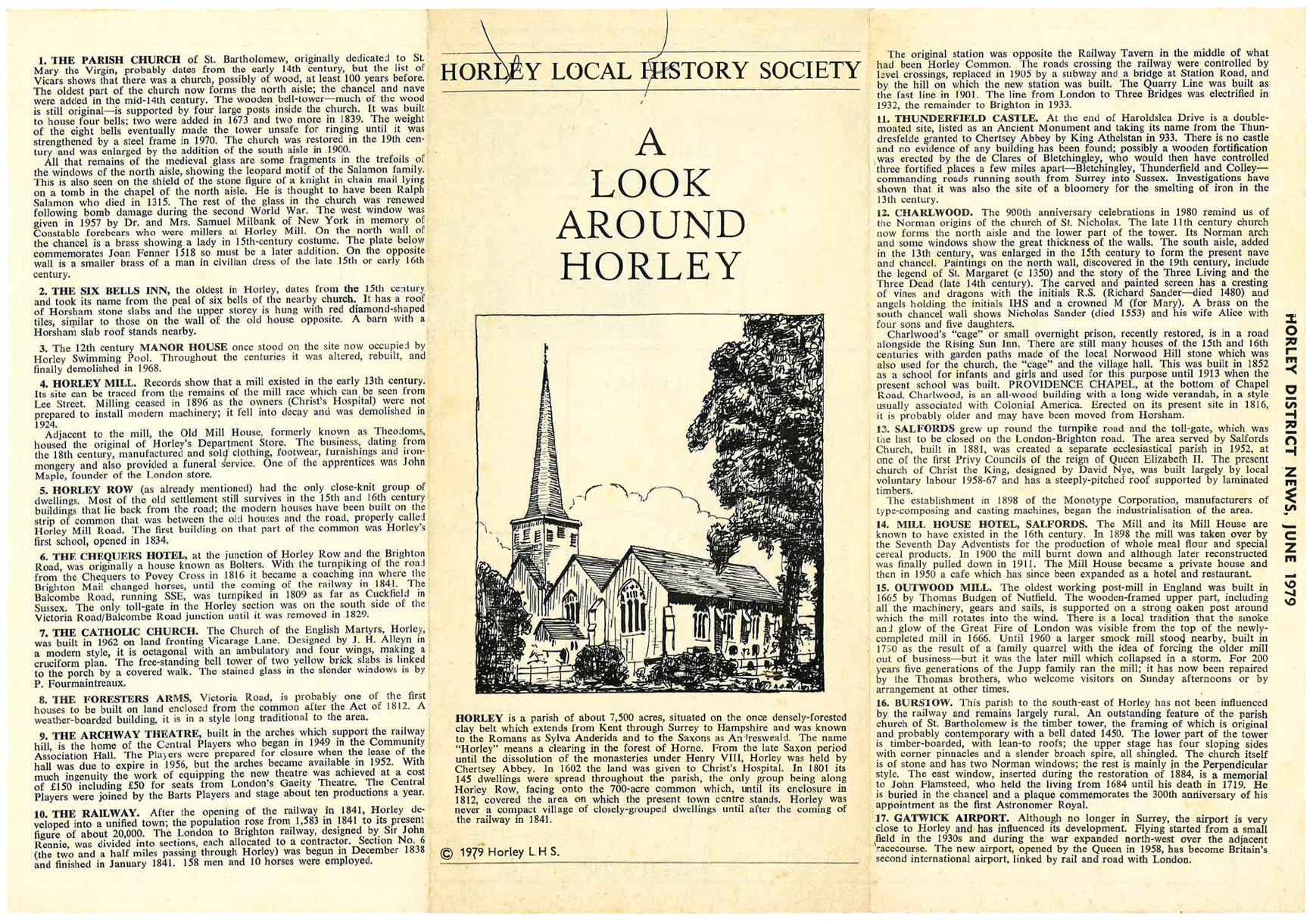

Horley, a history

Horley once predominantly provided agricultural services, to farms in the vicinity. Today, it primarily provides services to Gatwick airport and acts as a home for commuters to Canary Wharf, Westminster, Whitehall and, ‘The Square Mile.’

Horley lies within a geographical area known as the “Low Weald,” which is typified by heavy clay soils. The name “Weald” comes from Old English and means “forest”. In prehistoric times the whole area was thought to be densely forested and only penetrated by humans on summer foraging missions as, during winter it would have been, and in places still is, a quag mire that perennially suffers from winter flooding.

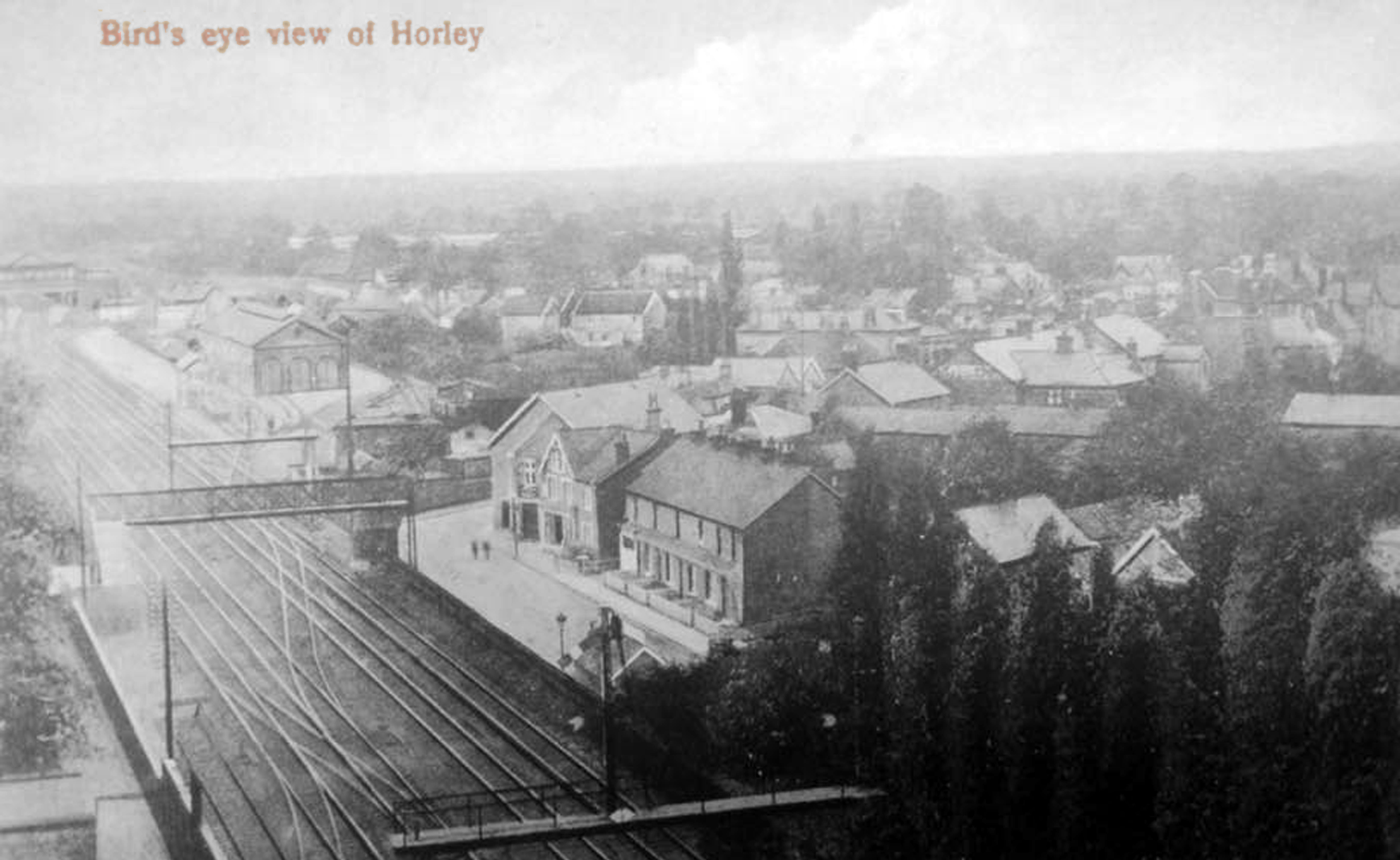

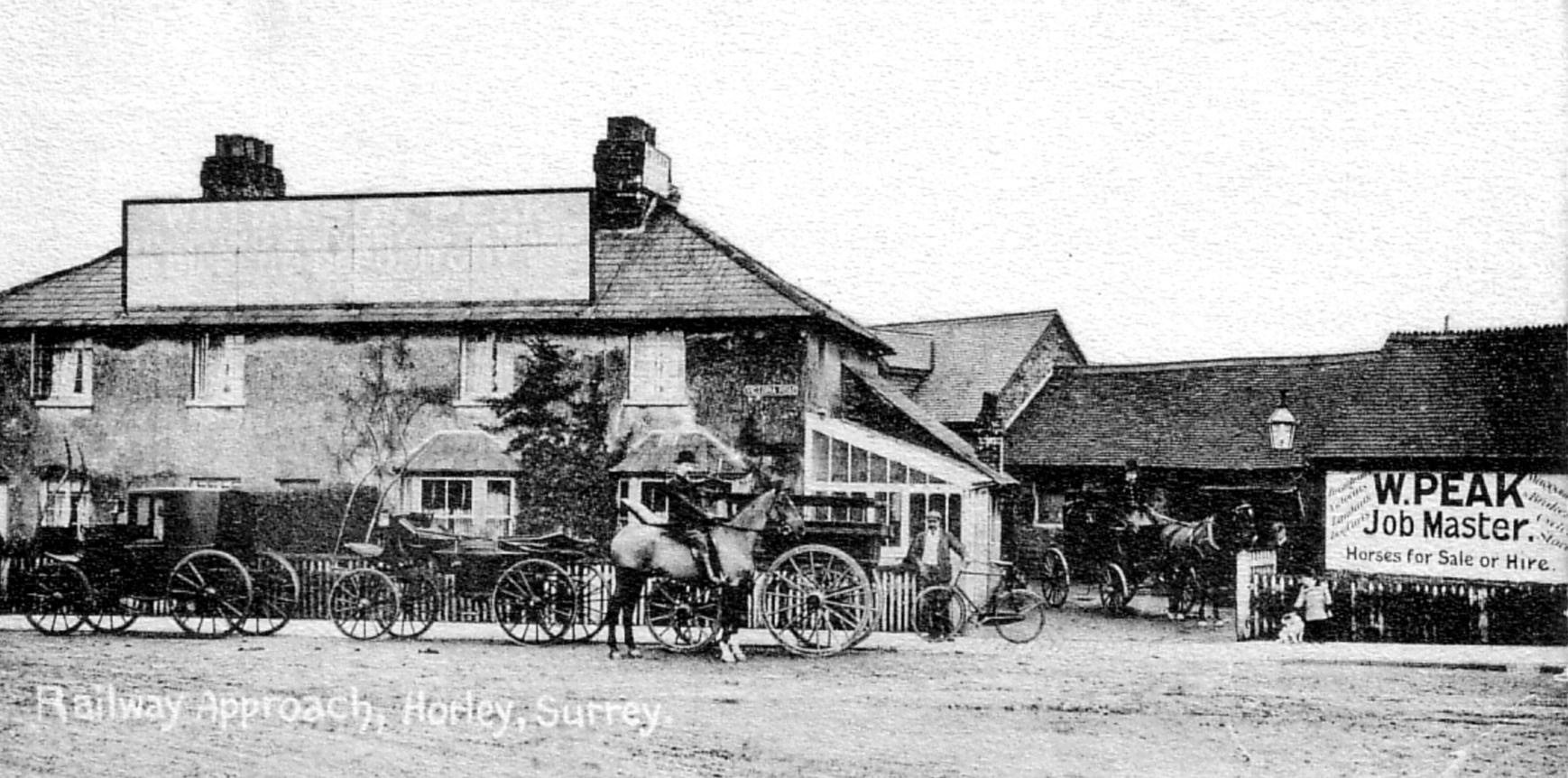

At first glance, Horley appears to be a modern, relatively small, town that has grown around a railway station built and opened in the early Victorian era (1841). However, Horley is actually very old. There have been settlements of sorts here (probably disparate) for over a millennia, partly on land that was once known as Thunderfield Common.

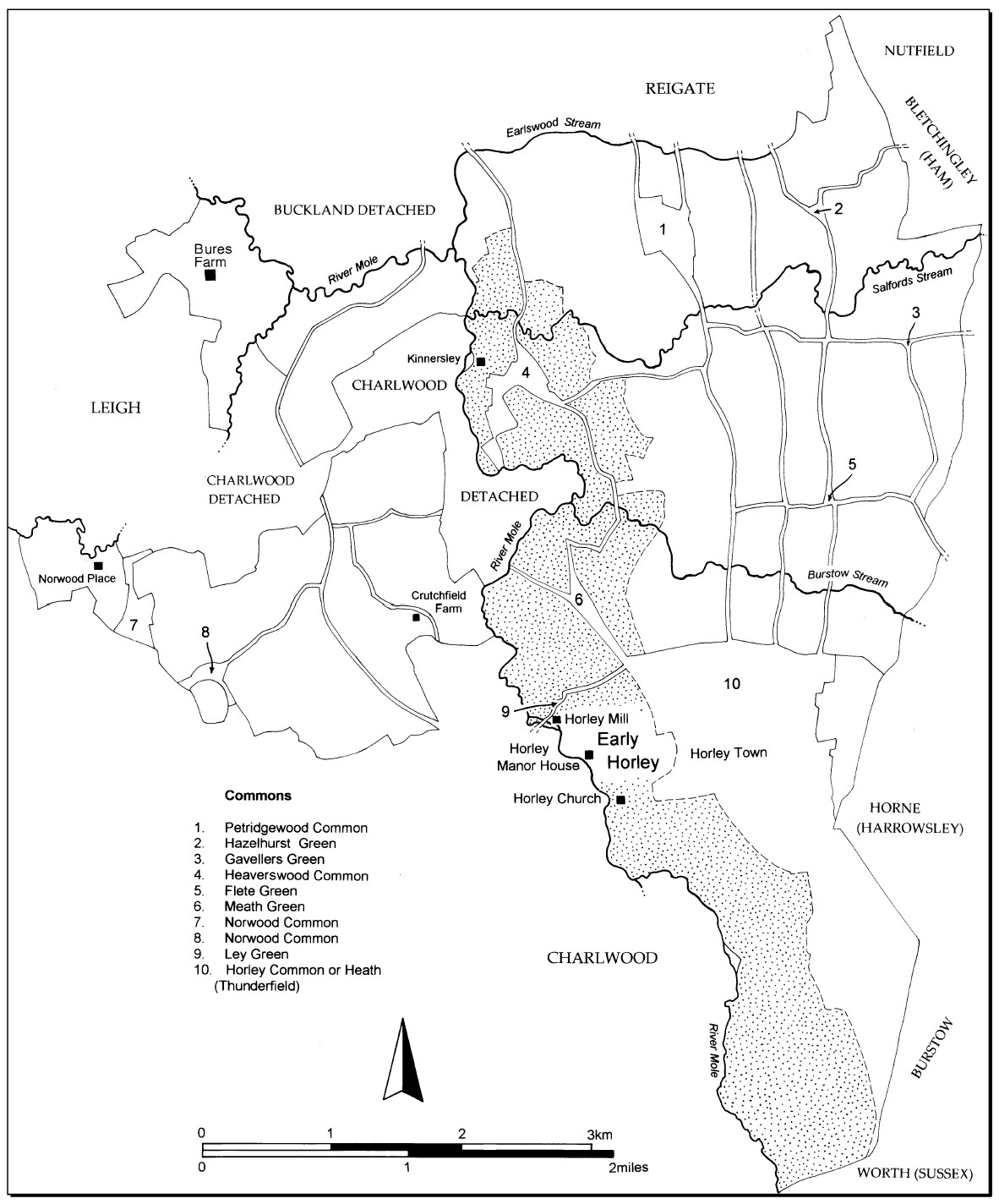

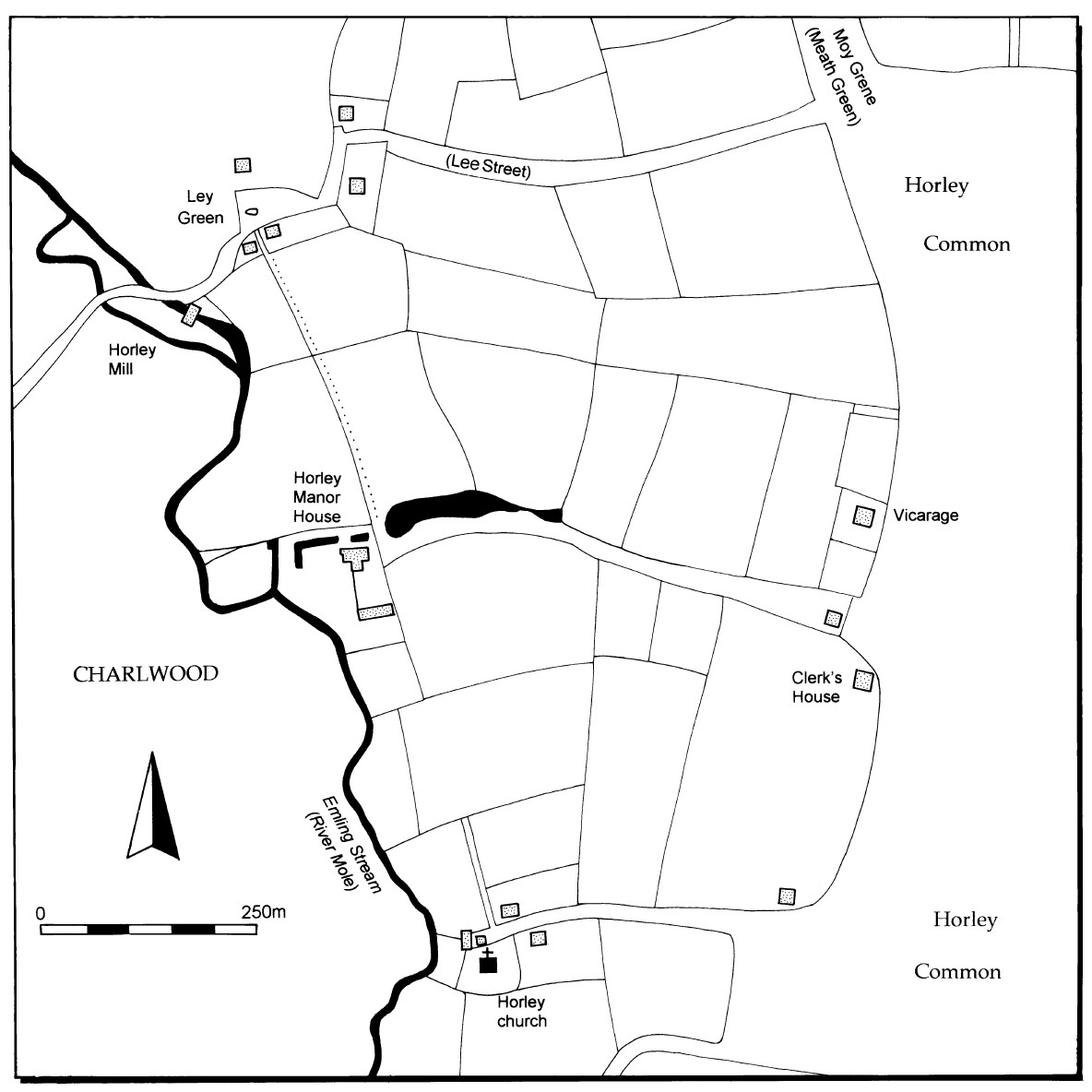

The ancient parish of Horley

Horley, c. 1602

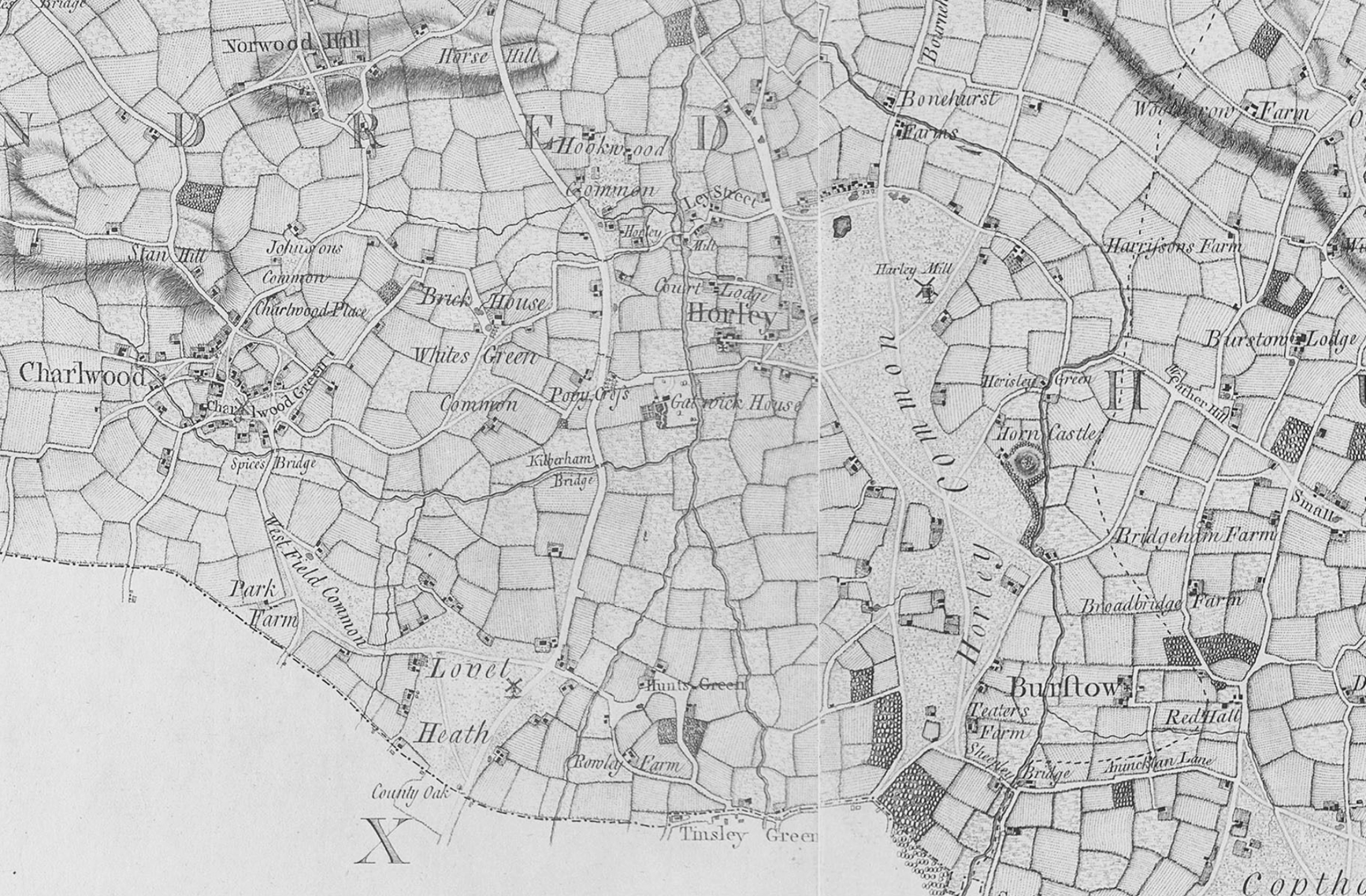

Horley on Rocque’s 1755 Surrey map

Horley, then and now

Horley in the 1920s

Horley in the 2020s

Horley currently has a population of around 20,000 but this number looks set to rise by quite a bit in the coming years. To the north there’s a new development, West Vale Park, that will ultimately, by hook or by crook, join Horley with the village of Salfords.

West Vale Park

To the east there are persistent rumors and probably active plans underway to build another suburb that will essentially link Horley’s neighbourhoods of Haroldslea and Langshott to the village of Smallfield.

Urban Surrounds

There is also proposed development to the south of Horley. Developers, at a minimum want to transform the fields and woodland outlined in red (on first of the below graphics) into a business park catering for the airport.

Expansion planes, plains, plans

Horley Business Park (proposed)

Gatwick Green (proposed)

Gatwick Green promotional document →

Bird’s-eye view, as it is in 2023

To the west there are plans to build another few estates around Hookwood/Povey Cross (these would serve to join Hookwood village to Horley even more emphatically than they currently are).

POLICY DS FORTY ONE

446 dwellings envisaged on former green belt 🙁

POLICY DS FORTY TWO

84 dwellings envisaged on former green belt 🙁

Mole Valley plans

RH: The Redhill postcode

The RH postcode area, also known as the Redhill postcode area, covers 20 postcode districts in South East England: East Surrey (including Redhill, Reigate, Betchworth, Dorking, Lingfield, Horley, Oxted and Godstone) parts of West Sussex (including Crawley, Gatwick, Haywards Heath, Billingshurst, East Grinstead, Burgess Hill, Horsham and Pulborough) and a small section of East Sussex (including Forest Row).

Horley, Gatwick Airport, Burstow and Smallfield are RH6. Crawley is RH10 and RH11.

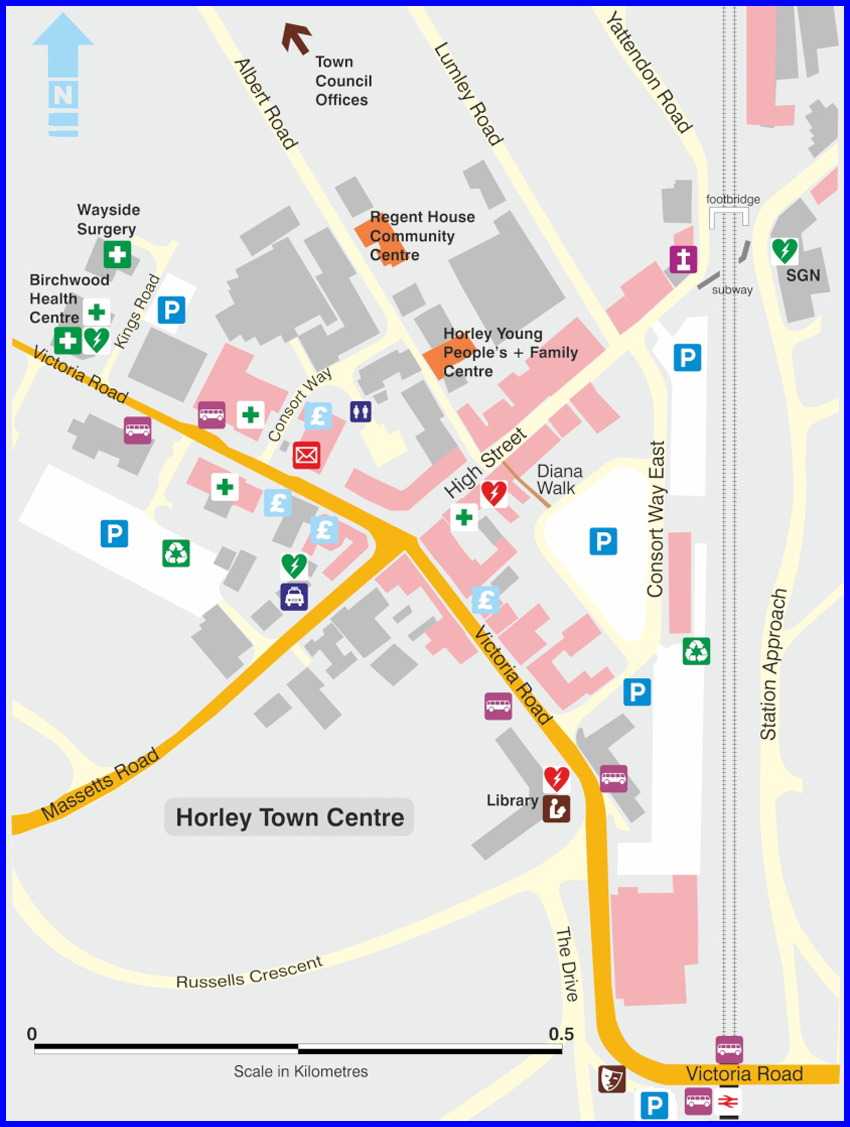

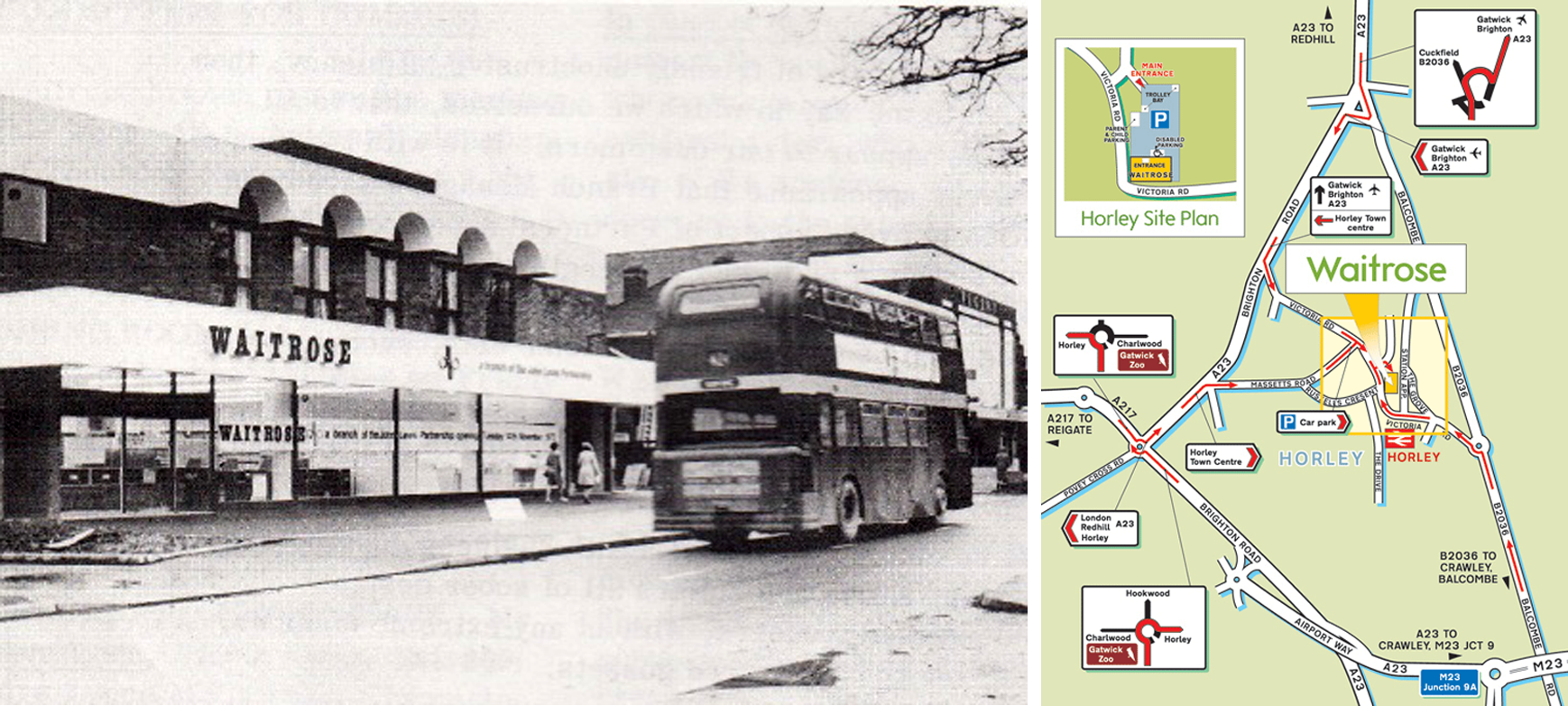

Horley town centre

Horley town centre lies to the west of its current and former railway stations. It offers Iceland, Lidl and Waitrose supermarkets and a surfeit of charity shops, coffee houses and coiffeurs—a “notorious” number, with little else besides, according to the town’s Facebook gossip groups, Horley Life and Horley Social. On the plus side, the town centre has a first-class public library and a quaint department store named Collingwood Batchellor that’s been trading since 1968. On the obverse, it has a permanently closed police station and several derelict former bank branch buildings.

Horley, its name &c.

Etymology

The study of the origin of words and the way in which their meanings have changed throughout history. Not be confused with either entomology—the branch of zoology concerned with the study of insects—or epistemology—the theory of knowledge, especially with regard to its methods, validity, and scope, and the distinction between justified belief and opinion.

According to the local masonic lodge—named “Haroldslea Lodge”—there is a connection between Horley’s name and King Harold II (reign, Jan. 1066 – Oct. 1066).3 This ties in with the probable fact that Harold II stopped over in Horley as he marched down from York toward Hastings and the south coast. This connection adds credence to a less probable, but persistent, ghost story: a legion of King Harold II’s battle slaughtered soldiers periodically march along a bridleway called Haroldslea to the south of Horley, that curves around the site of Thunderfield Castle.4

Haroldslea Lodge’s Messrs

Ten Sixty-Six

Haroldslea’s Ghost Story

Over the centuries Horley has been known as Haroldslea, Harrowsley and, Herewoldeslea. Horley’s name, first recorded in Anglo-Saxon writings of the 800s (the 9th century), is generally thought to have been derived from the words ‘horn’ and ‘leah’, as the town today is partly situated on what was once a “horn-shaped common”.5 A leah is an Old English word meaning: a clearing or a meadow; written as leigh or lea in Middle English. Spellings, from the late 12th century to c. 1300, are shared between variants of Horley and Hornley—in 1175 for instance, it is recorded as Hornleya.6

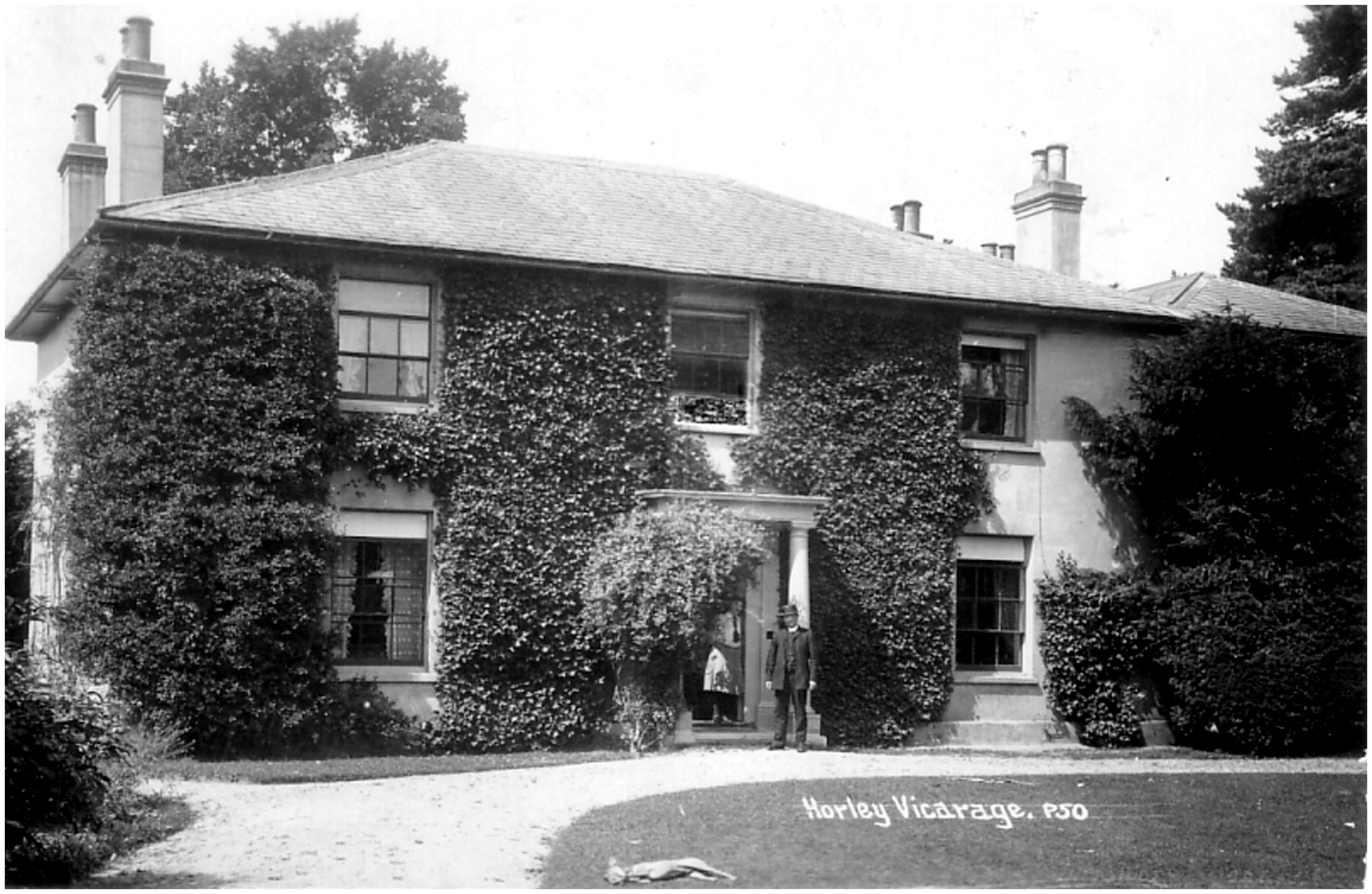

When Christianity first came to southern England during Anglo-Saxon times, Horley and its surrounds came under the control of the Benedictine Abbey of St Peter at Chertsey.7 Following King Henry VIII’s disbanding of the monasteries in the 1500s, the Horley and its environs was given as a grace and favour gift to a member of his royal court at Hampton.8

According to local historians, Horley extends to a much larger area than one might imagine. It roughly equates with that part of the ancient eponymous parish lying south of the Burstow stream (see map “The ancient parish of Horley”, above).9 To the west of the river Mole, past Tesco, Hookwood and Fairalls builders merchant, is the more rural sector of the parish which includes the old farms of Bures, Crutchfield and Norwood. To the north of Horley is the district of Salfords. Alas, with the huge West Vale Park housing development now well underway, Horley and Salfords are set to become a contiguous urban entity. As is said in Horley, “history is not a thing of the past.”

Horley’s surrounds, 1979

Another great trove of information on Horley, that also spells out an array of former names is a paper housed at The Institute of Historical Research:

Horley and emblems

Horley is one of the towns of Reigate and Banstead borough council (RBBC). RBBC is one of Surrey county’s eleven borough councils. Together these boroughs are the most wooded areas of England (Surrey has 22.4 per cent tree coverage compared to the national county average of 11.8 per cent), a fact reflected in the respective emblems and coat of arms.

RBBC’s coat of arms, officially granted on May 30th, 1975, is a combination of the elements of the Reigate shield, the device of Banstead and symbols of the parishes of Horley and Salfords and Sidlow. The motto “Never wonne ne never shall” (in other words: “We’ve never been conquered nor ever shall we be”) is taken from an ancient couplet and refers to the defeat of the Vikings by King Alfred in a battle in the Vale of Holmesdale—which runs through the counties of Kent and Surrey—in the 9th century.

King Alfred The Great

Never wonne ne never shall

The motto—“Never wonne ne never shall”—is rather ironic as the shield in the centre of the coat of arms has a background of blue and yellow chequers taken from the arms of the de Warenne family of France (de Warenne accompanied William the Conqueror and after their victory over the English in 1066, was made the first Earl of Surrey).

Against the Frenchman’s blue and yellow chequers is the Reigate Castle Gate and oak tree. The top of the shield has a golden woolpack between two sprigs of oak. The woolpack refers to the former importance of sheep rearing and wool production in Banstead. The oak sprigs on the coat of arms represent the two parishes of Horley and Salfords and Sidlow. Above the shield is a helmet with a wreath and draped cloth. On top of the helmet is a pilgrim referring to the ancient route along the escarpment of the North Downs by Banstead and Reigate, the Pilgrims’ Way (Canterbury to Winchester).

On either side of RBBC’s shield is a white lion and a white horse. The lion comes from the arms of the de Mowbray family who were briefly Lords of the Manor of Banstead in the 12th century. The horse refers to the tradition of horse racing on Banstead Downs in the 17th century and immortalised in the Oaks race of Epsom Derby Friday.

On the necks of the animals are wreaths again in the blue and yellow of the de Warenne family. On the shoulders are roundels of blue and white waves indicating the River Mole in Horley and Sidlow. The roundel on the lion has a tanner’s (or flaying) knife, the emblem of St Bartholomew, the patron of Horley, who is said to have been flayed or skinned before he was crucified. The roundel on the shoulder of the horse has a sallow leaf, a reference to Salfords, which is derived from Sallow Ford. The Sallow tree is commonly known as Pussy Willow.

Horley’s Patron Saint

Horley, Gatwick & Controversies

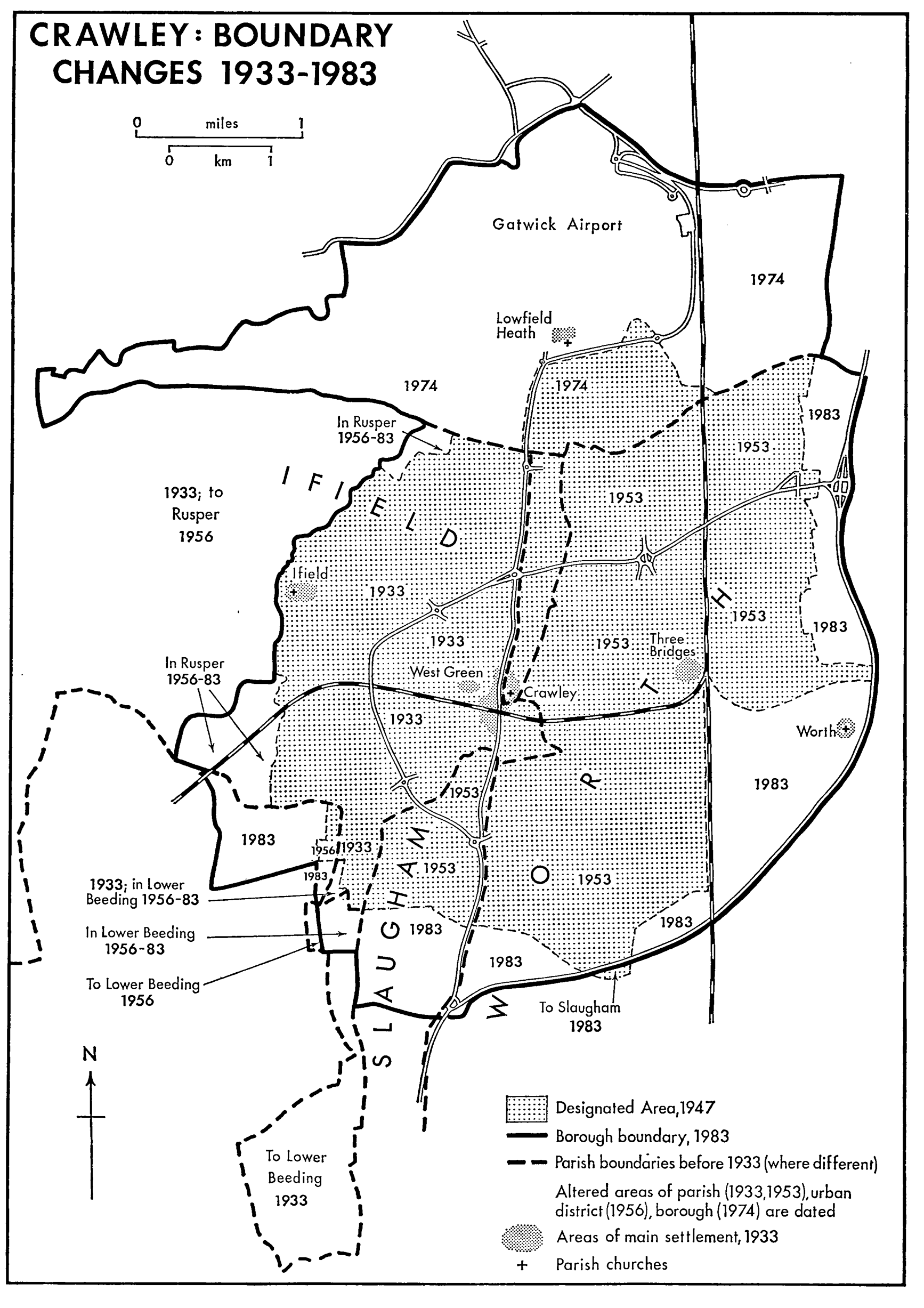

Considering Horley is right under Gatwick airport’s flightpath—with over 33 million passengers annually and the world’s second busiest runway, clocking up an average of 700 daily flights—it is a little grating to learn that the airport was once part of Horley town council’s parish but was arbitrarily taken and given to Crawley borough council by way of a 1972 Government decree.

Gatwick’s logo

Gatwick’s brand

A bird’s-eye view, snapped in 2022

In the 1970s, Charlwood, Gatwick and Horley were ‘moved out’ of Surrey and into West Sussex as part of the Local Government Act of 1972. It should not come as much of a surprise but, most people in the Horley area were rather put out by this.

Protesting in the road, rightly so

Glorious Gatwick has long been close to the hearts of Horley residents. Gatwick was once a horse racing venue—one that hosted to the Grand National several times—and, it was Horley that catered to the crowds that came to party and flutter and, patronise the “flights for fun” services of the Surrey Aerodrome Club (housed at Gatwick Manor Farm) in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Horse play, no more

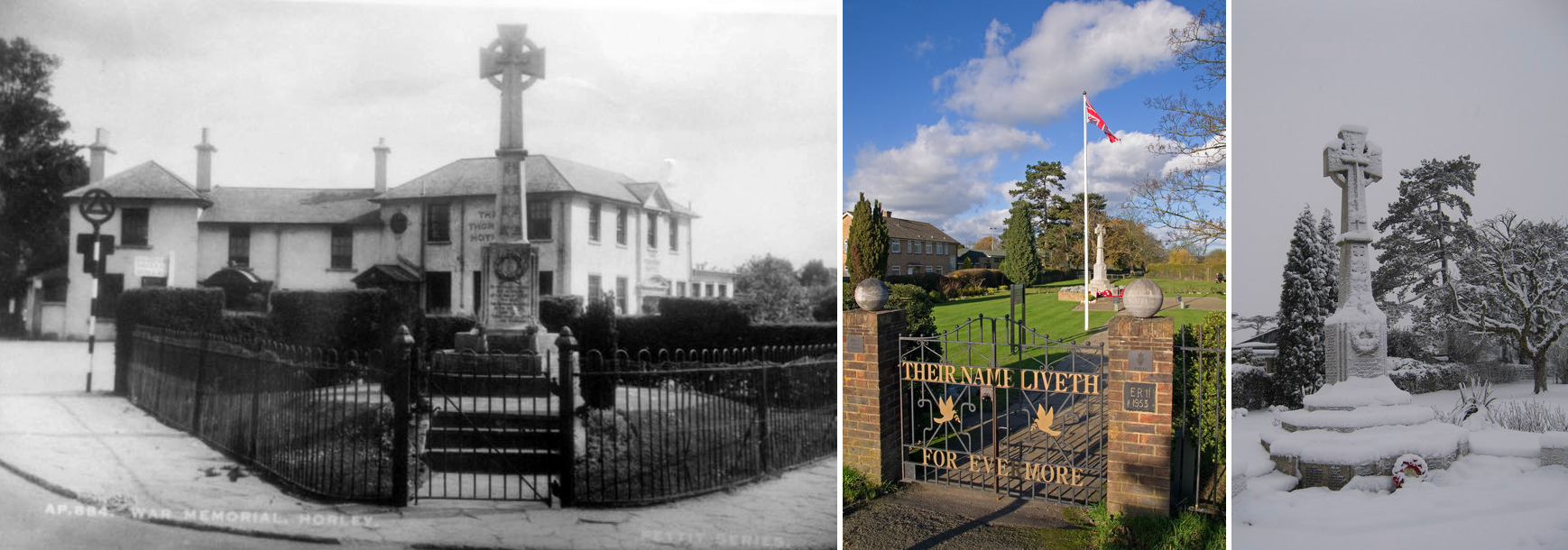

The Horley Millennium Mosaic (see below) was commissioned by Horley Town Council and was unveiled on the 2nd of December, 2000. It was designed and made by the Mosaic Workshop on Holloway Road, London, and paid for by local builders’ merchants, Mitchells of Horley, who were celebrating their centenary that year (they’ve now unfortunately closed down for good).

The mosaic, situated on the town’s partly pedestrianised High Street, is telling in that it prominently weaves the airport into Horley’s very fabric. As locals say: the bond between Horley and Gatwick is here set in stone.

Horley’s Y2K Mosaic

Ordinance Survey (OS) Grid Reference: TQ2843

As the 1964 aerial snapshot below shows, Horley is immediately to the east and north of the airport. A number of Horley neighborhoods are depicted in this photograph: in the top-left are Court Lodge and Meath Green, at the top, in the centre, is Horley Central and below it, Gardens Estate, and Haroldslea is at the top, to the right of the London–Brighton main railway line.

Horley/Gatwick

Maps speak volumes too:

The airport’s on our doorstep:

The Charlwood & Horley Act, 1974

In an exception to the rule, residents of Horley and Charlwood were granted the right to have a one-time vote on that nationwide boundary redrawing exercise and, by a large majority, elected to once more be part of Surrey.

The Charlwood and Horley Act 1974 was an Act of the Parliament that amended the Local Government Act 1972 to move the village of Charlwood and the town of Horley back to Surrey.

On 17th October, 1973, it was announced that the Government would be holding negotiations about the Surrey/West Sussex boundary. The Charlwood and Horley Bill was introduced to Parliament on 31st October, 1973. It passed all stages on the last day of the parliamentary session and received royal assent on 8th February, 1974.10

However, the Government decided not to relinquish Gatwick back to Surrey. It follows that since then, and until today, some of the taxes LGW pays go to Crawley, not Horley town council.

Crawley creeps up on Horley

Gatwick’s clearly next to Horley:

It happened again in 1990

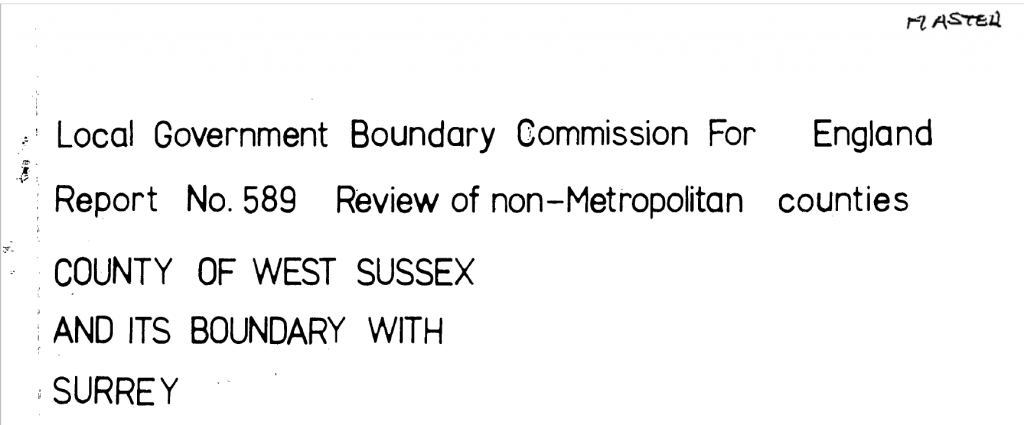

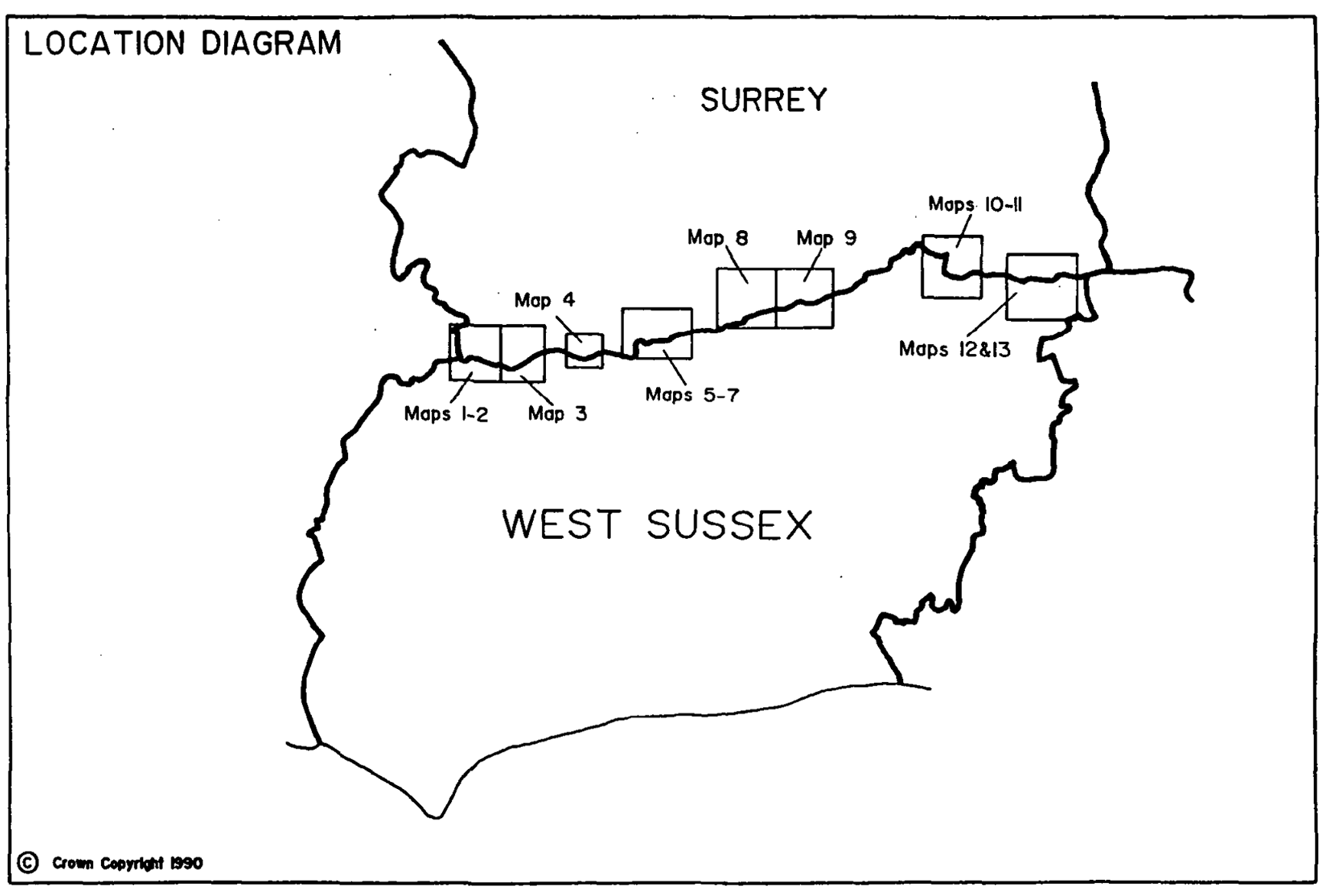

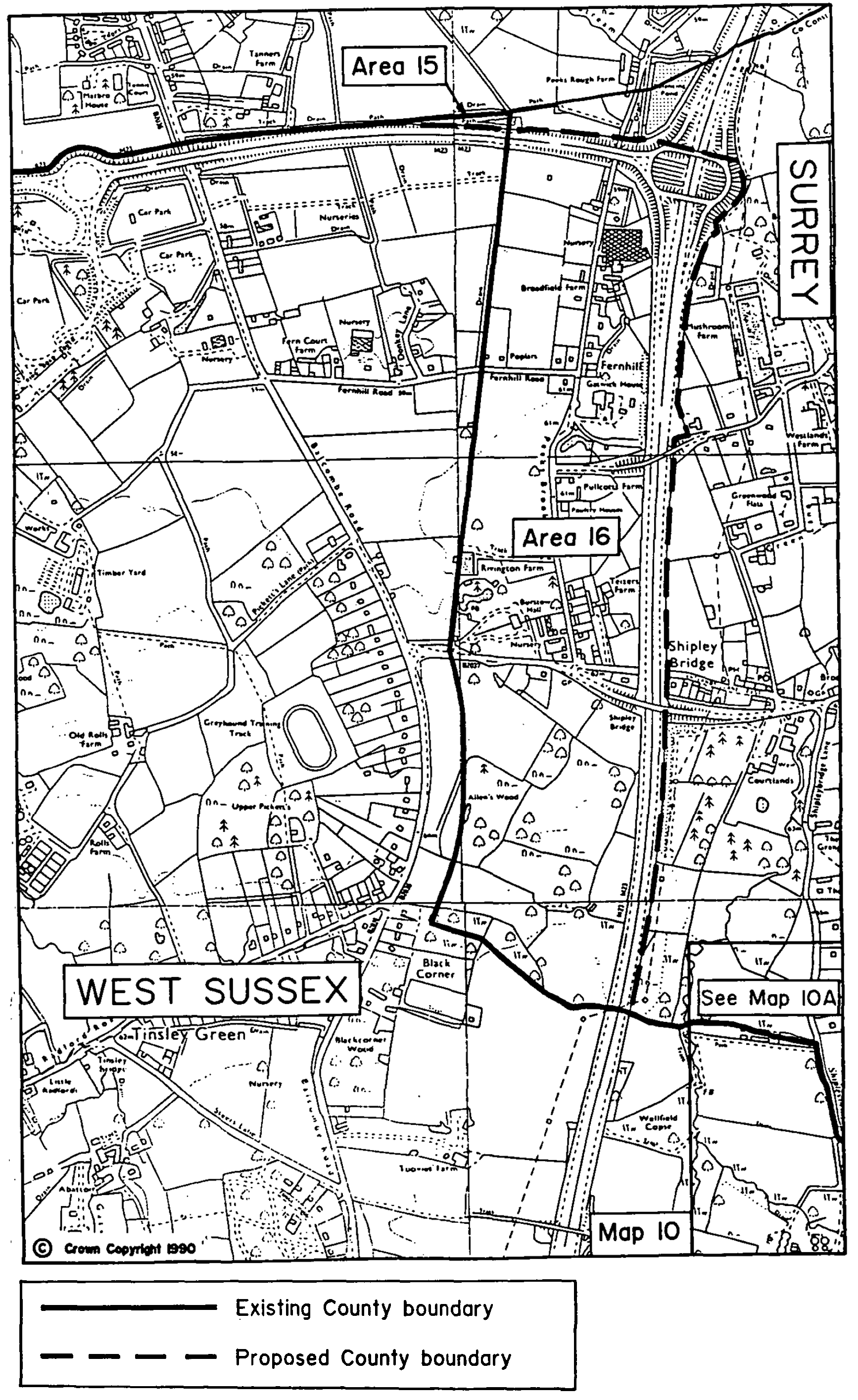

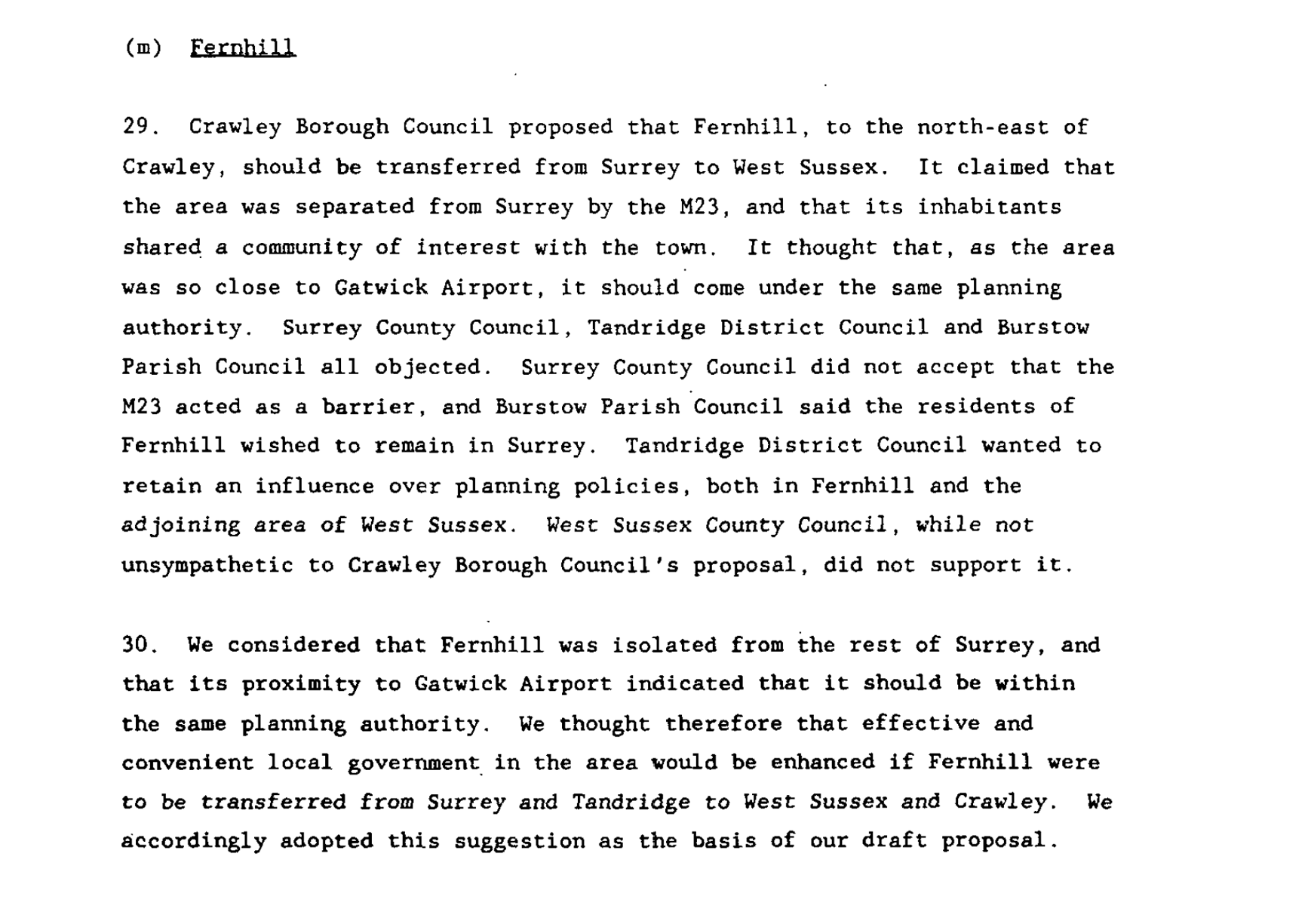

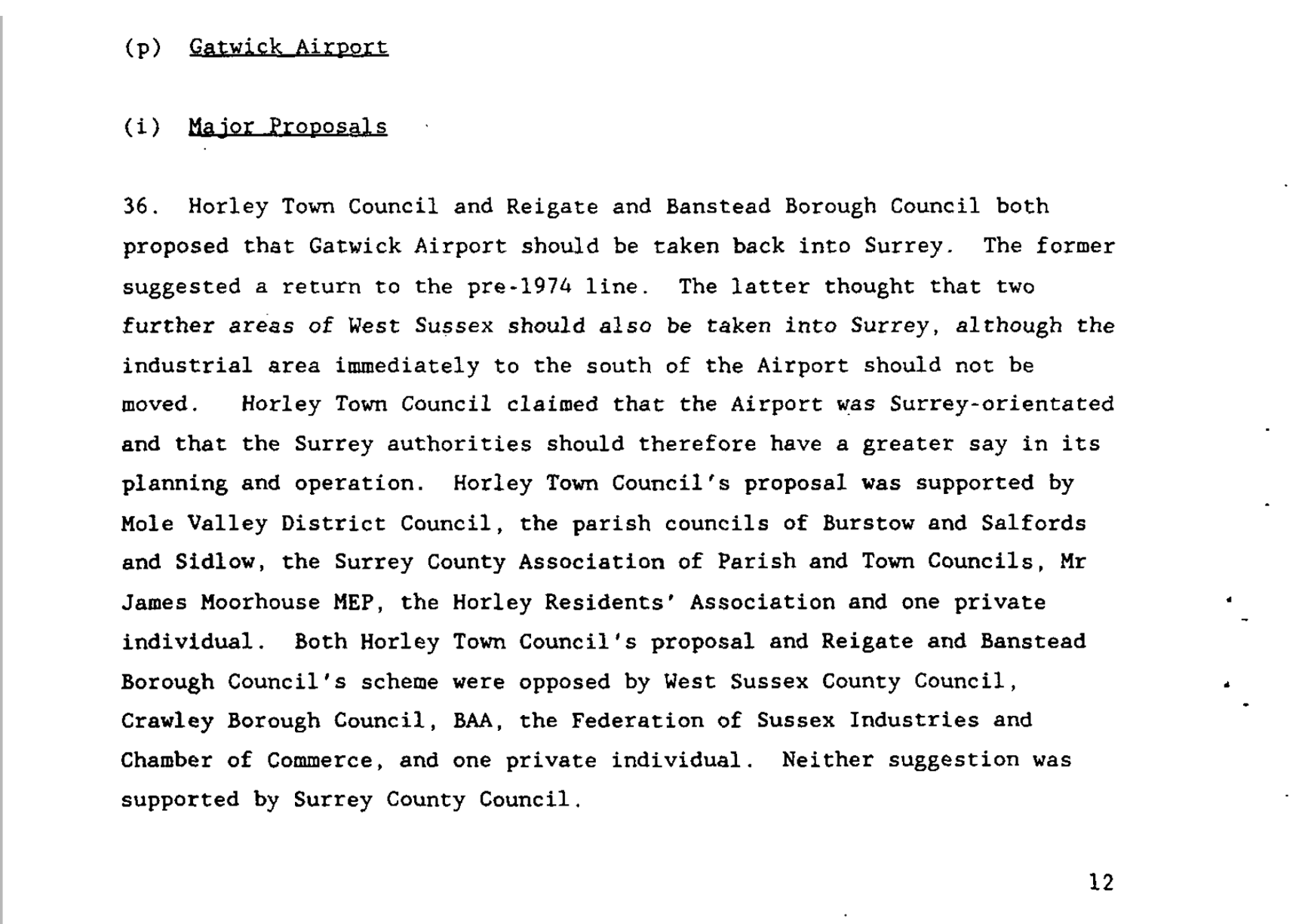

Again in 1990, as part of further county boundary realignment shenanigans, parts of Horley parish were reclassified as no longer being in Surrey but that day on being considered as hamlets of West Sussex.

Report No. 589, 1990

1990 boundary change map

It might not be Area 51, but nonetheless

Extract (01)

Extract (02)

Extract (03)

Extract (04)

Extract (05)

Council boundary map, 2023

* * *

There was/is further controversy—over and above the county lines, boundary changes of 1972 and 1990. This relates to the ever expanding airport itself.

In the aftermath of the war RAF Gatwick reverted back to civilian use, its mostly grass runways were often quag mires and its viability hung in the balance, both Redhill and Croydon were considered to host London’s principle hub airport, Gatwick wasn’t even a contender, in the event Heathrow, which was countryside, with hamlets, at the time was chosen. However Gatwick airport had backers and, in the early 1950s, residents of Charlwood and Horley, were given assurances that their homes wouldn’t be bulldozed by Gatwick seeking to become a rival to London’s newly opened and de facto hub airport, Heathrow. Back then, the backers of Gatwick airport only publicly sought a licence to accept flights intended for Heathrow if/when conditions there were too foggy.

However, as soon as Gatwick was granted the right to act as an overflow airport, it then submitted plans (probably already well hatched in private) that would have made it bigger than Heathrow. The map below shows plans set out in 1952. Had those plans gone ahead in full, Charlwood would have been wiped from the map.

Grand ambitions back in 1952

By the mid-1950s Gatwick had been granted the right to act as London’s second airport however, it was told it could not fulfil all of its ambitions immediately. In the event it completed the second stage (charted on the map above) and then decided to build North terminal on part of the area that had been penciled in for being the first stage. Charlwood was given a reprieve from the bulldozers but from the 1960s onwards the noise and congestion would grow and grow.

LGW’s Noise Insulation Scheme

Gatwick’s Strategic Noise Maps (PDF) →

40 years have since passed and Gatwick now has an array of expansion plans on the table (and probably under it too). The moratorium on the idea of a second (or third) runway has expired. It is evident that a effort is underway to petition for a substantial increase in the capacity (and size) of London Gatwick.

In the photograph below, a second runway is clearly seen. It can, under certain circumstances, be used but it’s too close to the main runway to be permitted for continuous commercial use at present. However, those regulations may change (1) and if not (2) plans are afoot to expand the airport to the east, west and south to accommodate a new ‘second’ runway and a third terminal.

Horley, Gatwick and additional runways

Gatwick’s Plans

The consortium that own the airport are actively trying to get permission to expand. One plan is to widen somewhat the gap between the two runways. However, residents are concerned that this will require another land grab (e.g., between Hookwood/Povey Cross and Charlwood and, the areas to the south and to the west).

Grand designs…

…for doubling current capacity

An artist’s supposition

Further artists’ suppositions

Looking south

Again, looking south

Now we’re looking northward

Extract A, from a 2018 plan

Extract B, from a 2018 plan

Selected documentation

01. A Second Runway, April 2014

02. Runway Options, July 2014

03. Draft Master Plan, 2018

04. Master Plan, 2019

05. Environmental Report, 2021

06. Consultation, Summer 2022

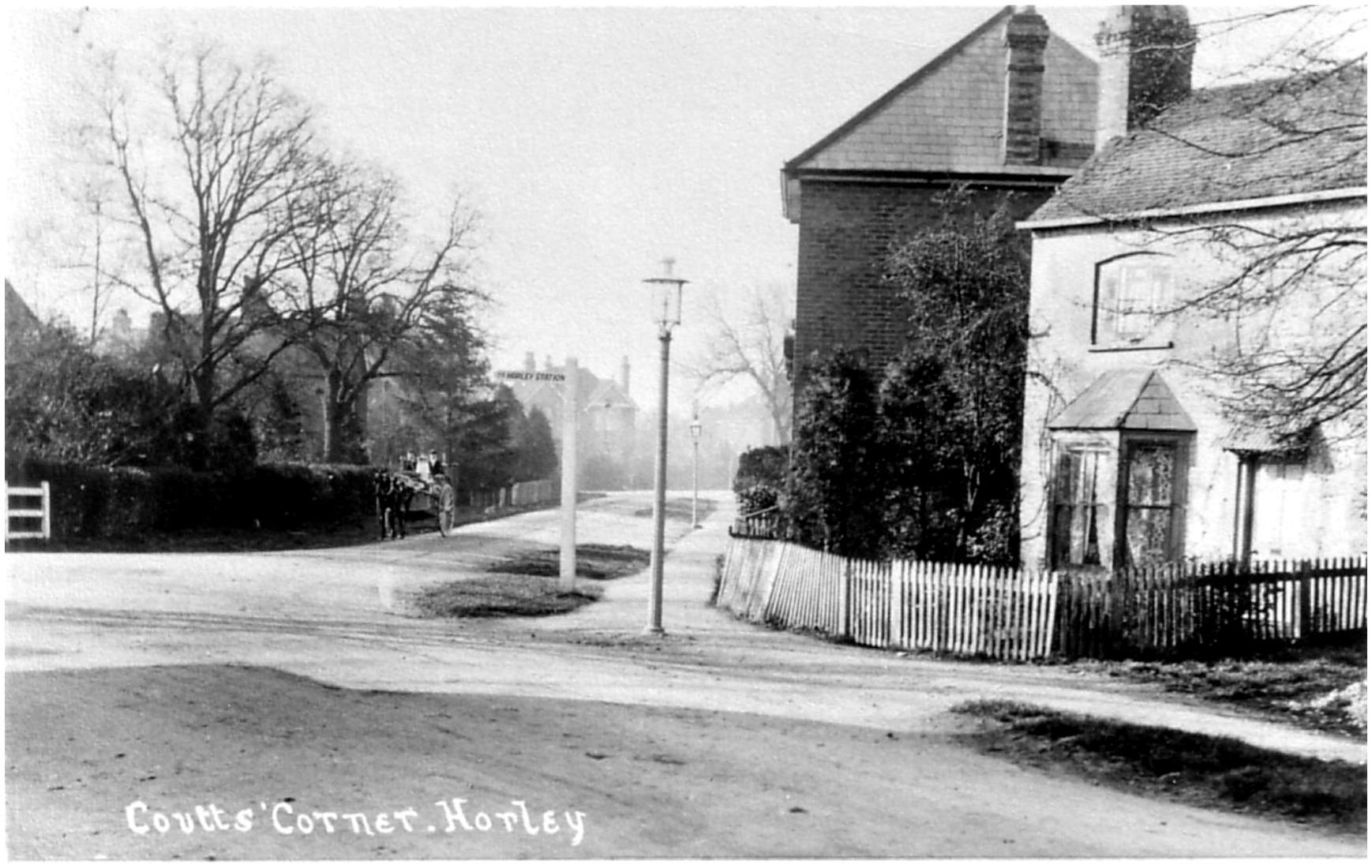

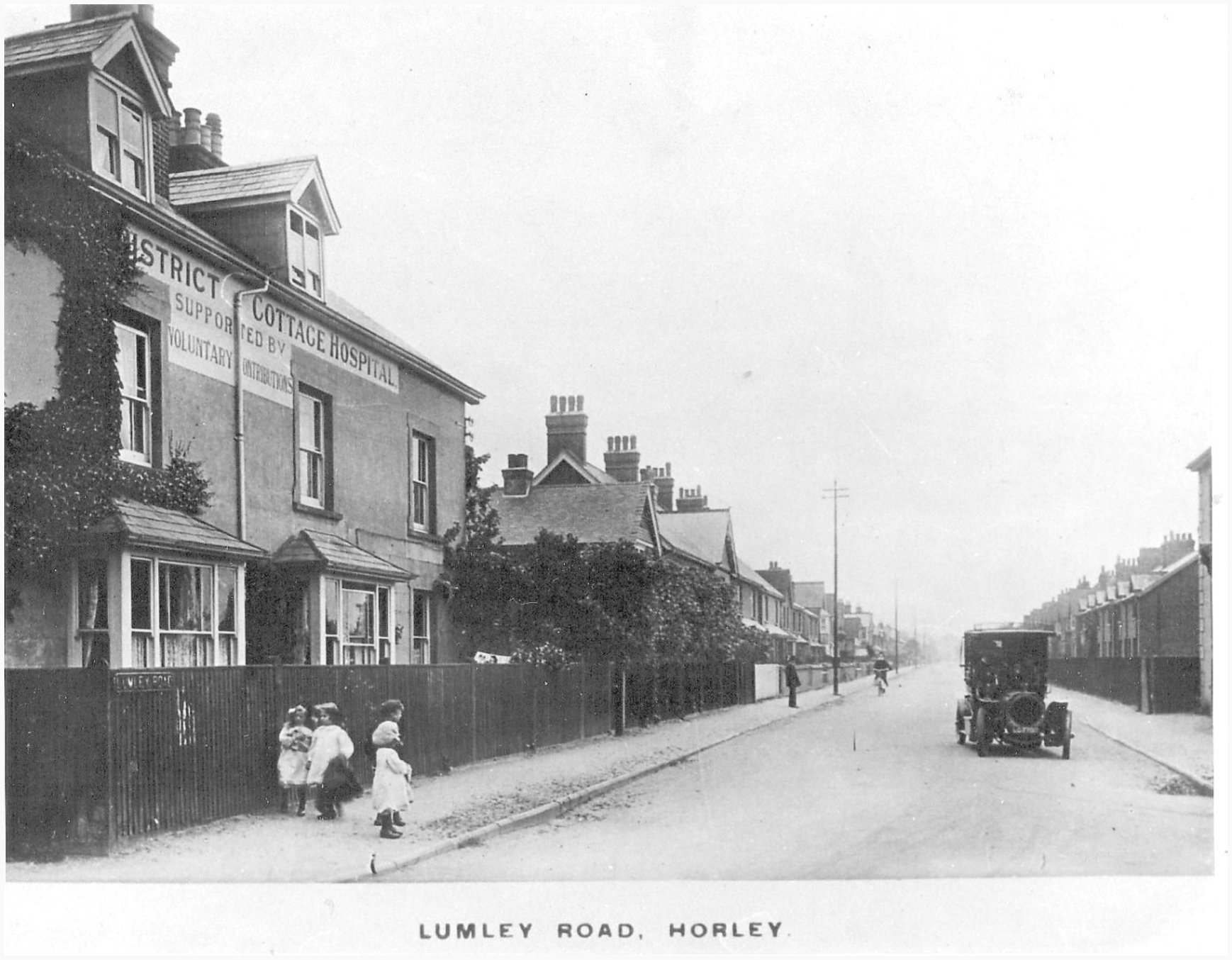

Horley in pictures

Don’t bank on it

Services

The High Street

Commerce

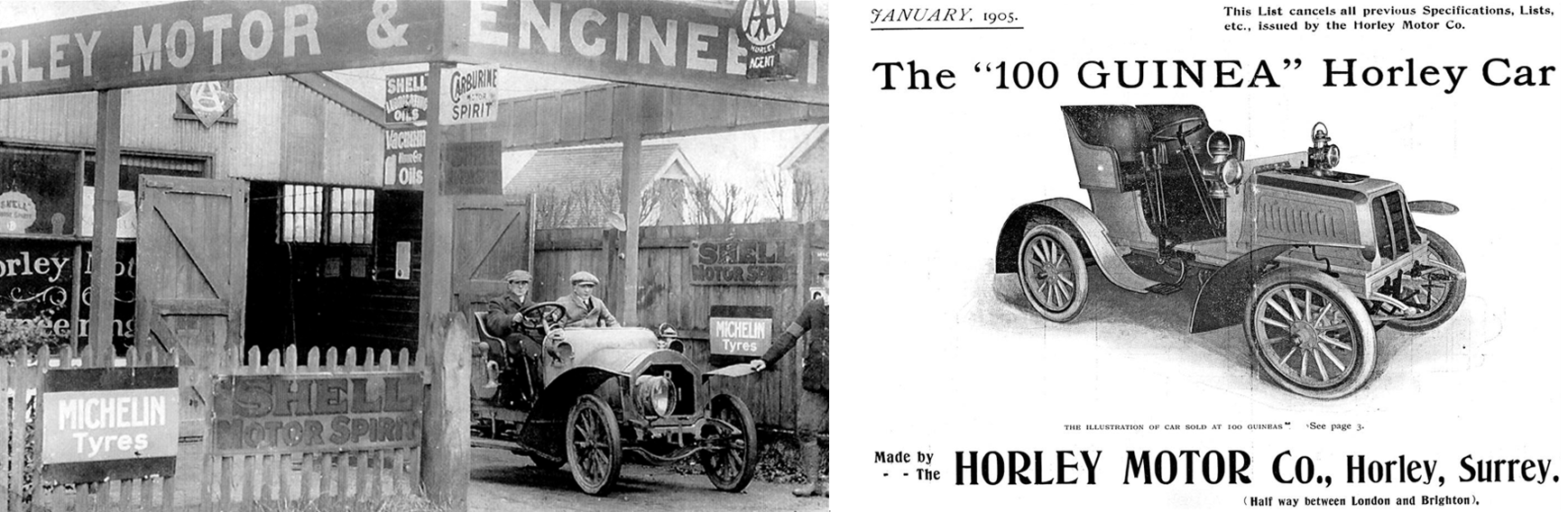

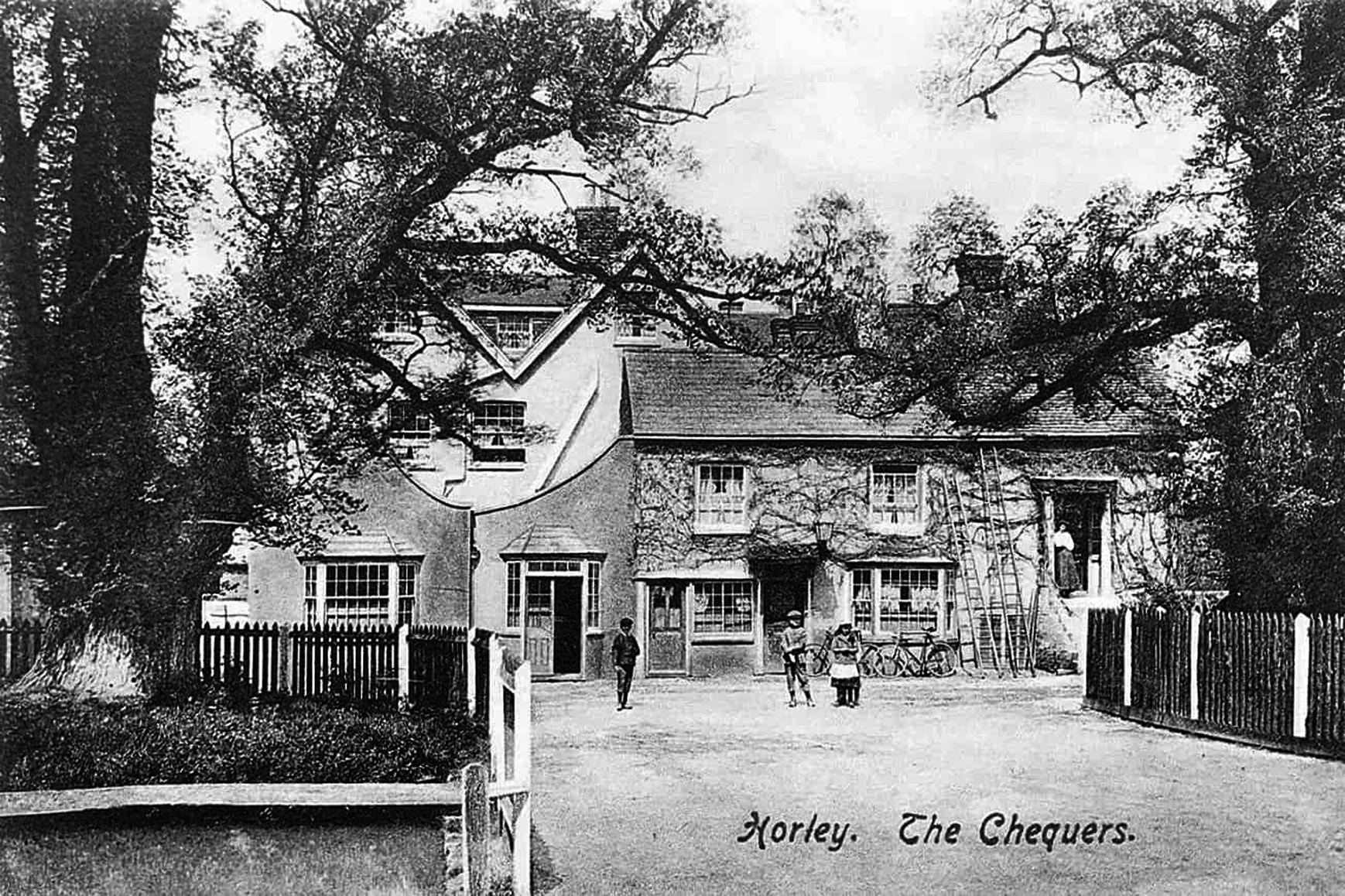

In 2020, Forgotten Spaces explored the once abandoned “Chequers” public house and adjoining Menzies London Gatwick Hotel.15

On the road

(Fishers Farm, 17th century, Grade II listed building, c. 1910).

Once forming the western boundary of Horley Common, a few old cottages that fronted the common edge still remain on the lane today.

Horley, Maps & Cartography

Horley on the map

X/Y co-ords: 528476, 142991

Lat/Long: 51.17169952, -0.16365091

Height: 56.7m

District: Reigate and Banstead (RBBC)

County: Surrey

Region: South East

Country: England

Horley & its surrounds

Horley, up close

Horley, from afar

Horley, macro

Horley, telescopic

Horley, circa 1750

Rocque’s Surrey Map →

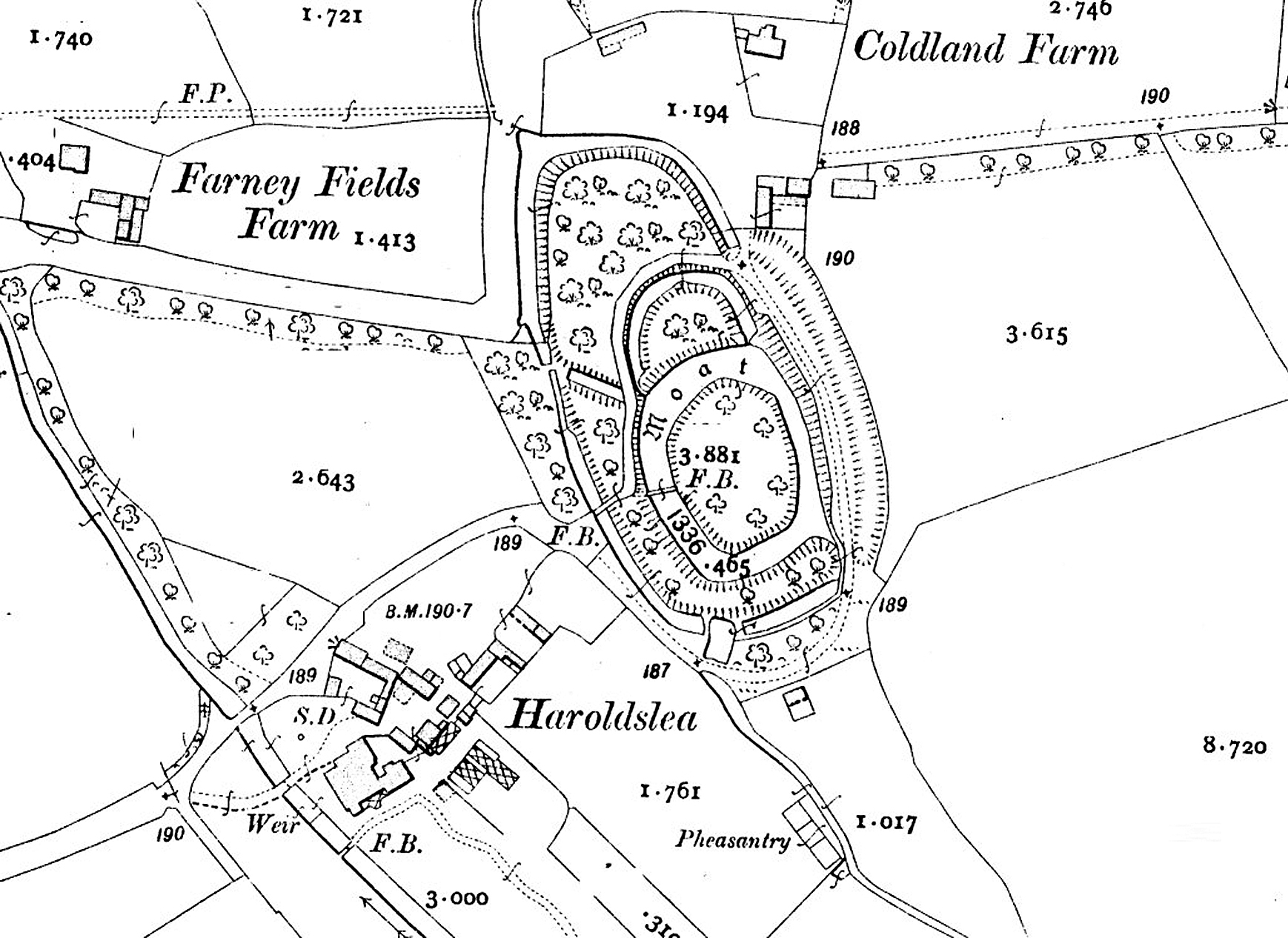

On the map above, Gatwick House and Hunts Green are noted (site of Gatwick airport today) and we see the extent of Horley Common and Horley town too. The road dissecting the common is very much in line with today’s Balcombe Road. To the right of that road Horn Castle is noted (more commonly referred to as Thunderfield Moat/Castle today and now part of the Haroldslea neighbourhood) as is Horley Mill and Herisley Green Farm—today’s Harrowsley Green Farm (Grid Ref.: TQ289433). The the left of the road dissecting Horley Common, we see another Horley Mill (water as opposed to wind), Ley street (today’s Meath Green) and Court Lodge Farm (Court Lodge). Povey Cross is there too and Brick House, to Povey Cross’s north west, was once a brick factory and today is Tesco Hookwood (Grid Ref.: TQ2709042670).

Horley (south), 1911

Horley (north), 1938

An extract of MapCarta, 2023

Image: 13 MB (5,559 by 5,939 pixels).

An extract of OpenStreetMap, 2023

Image: 18 MB (7,635 by 6,061 pixels).

Cartography

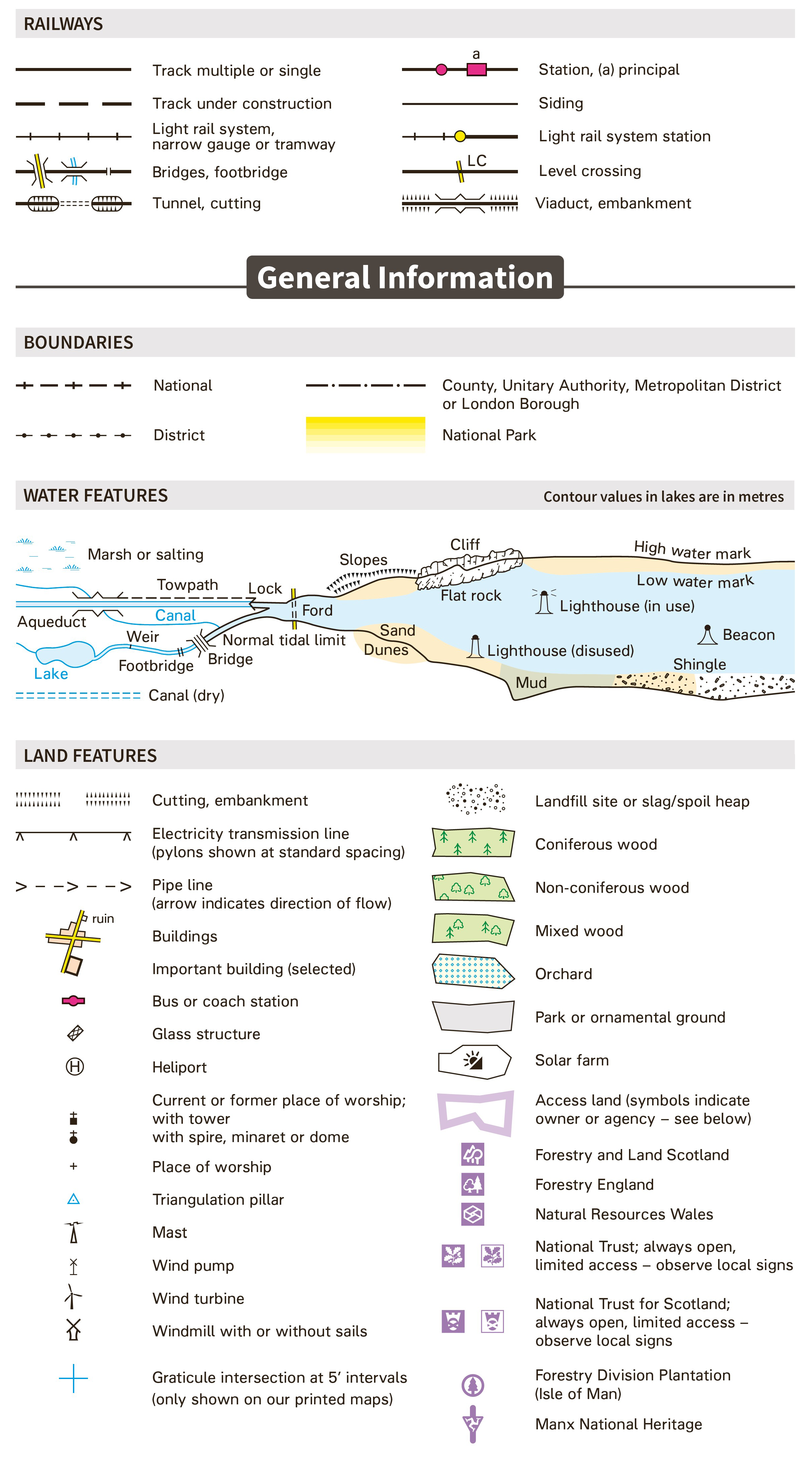

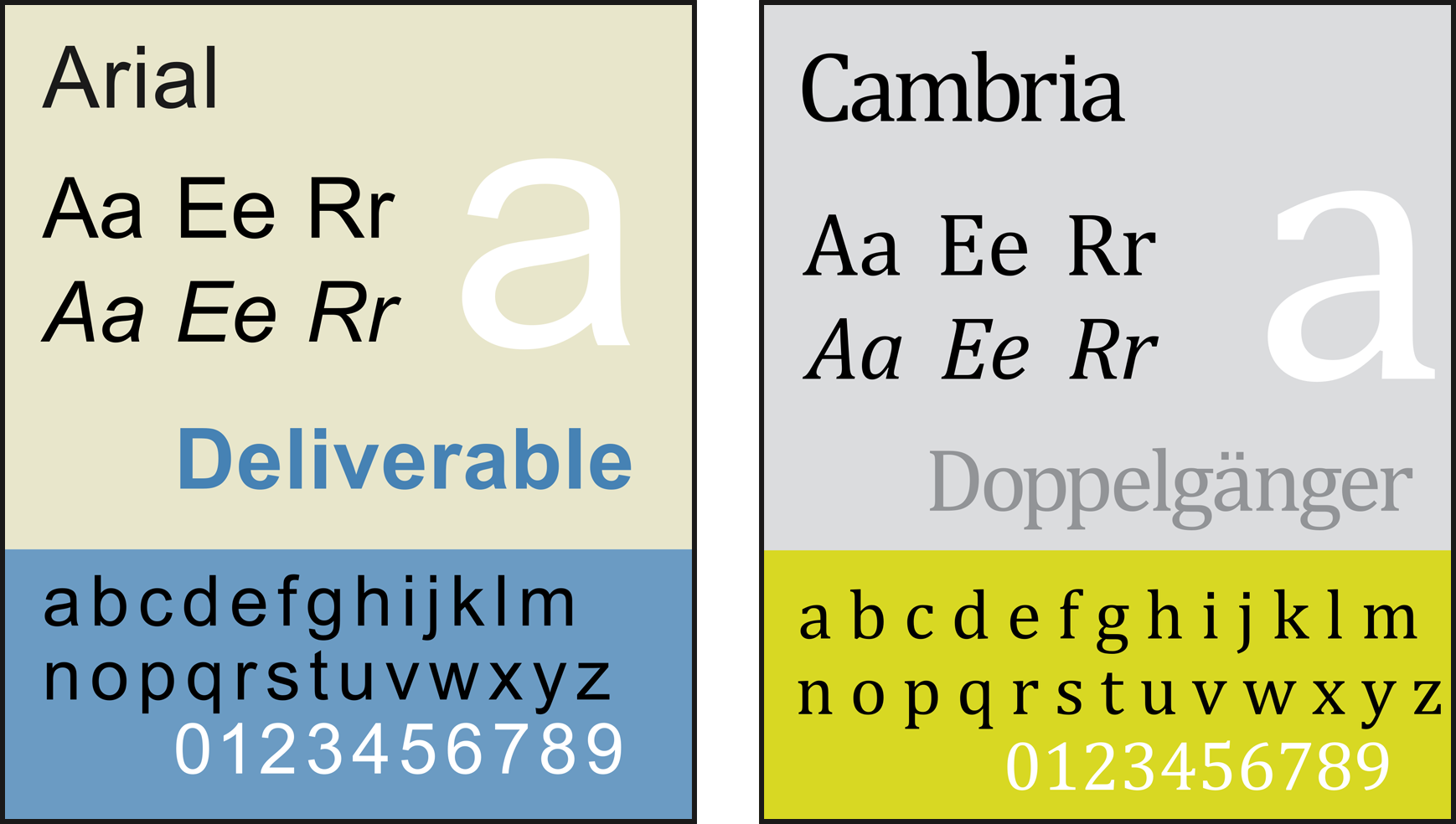

Cartography is the art, science, and technology of map making and, the Ordnance Survey (OS) is the national mapping agency for Great Britain.

According to the OS, “maps are graphical or symbolised representations of reality.” The form a given map takes depends in large part on what it is going to be used for. For example, map tailored to avid hikers navigating complex mountain terrains would be very different from a map used to show the split of votes across a country after an election, or the migratory route of butterflies between climatic zones.

Horley sits within OS Grid: TQ 2847 4299

Horley can be found in the following OS Map: 146: Dorking, Box Hill & Reigate

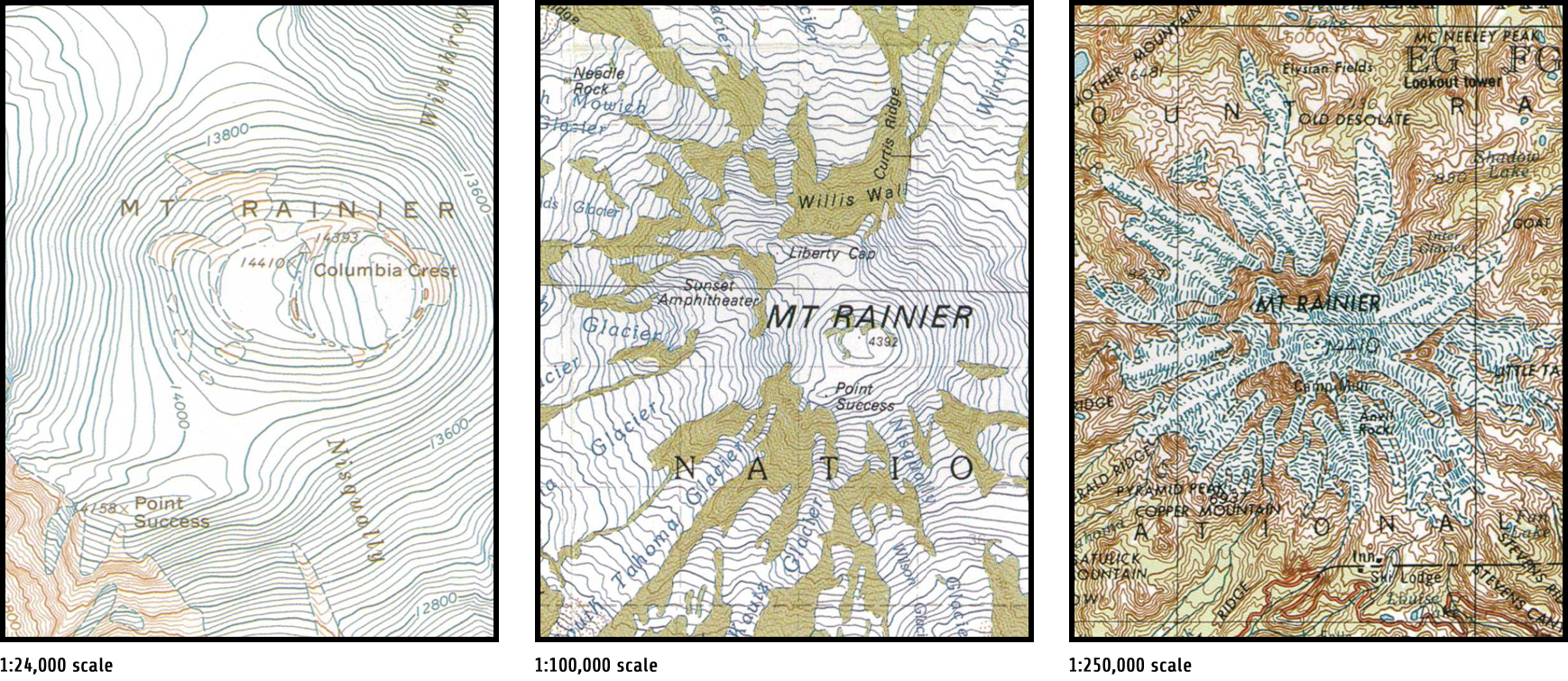

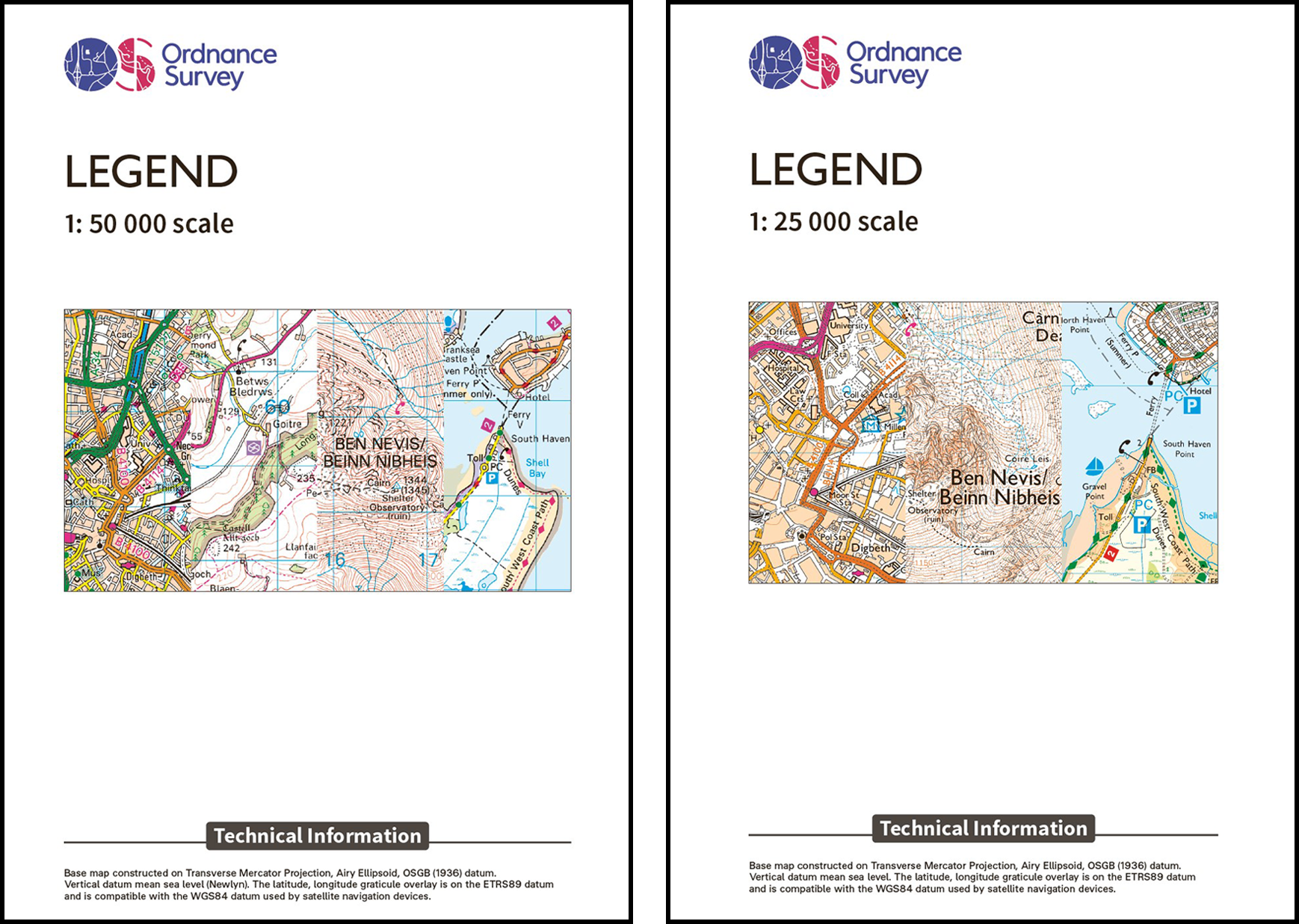

Map scales

OS Landranger Maps have a 1:50, 000 scale (and show roads, large paths and some individual features) while, OS Explorer Maps have a 1:25,000 scale (and show many features including paths and buildings over a small area). If the scale on a map is 1:25 000, that means that every 1cm on the map represents 25 000 of those same units of measurement on the ground.

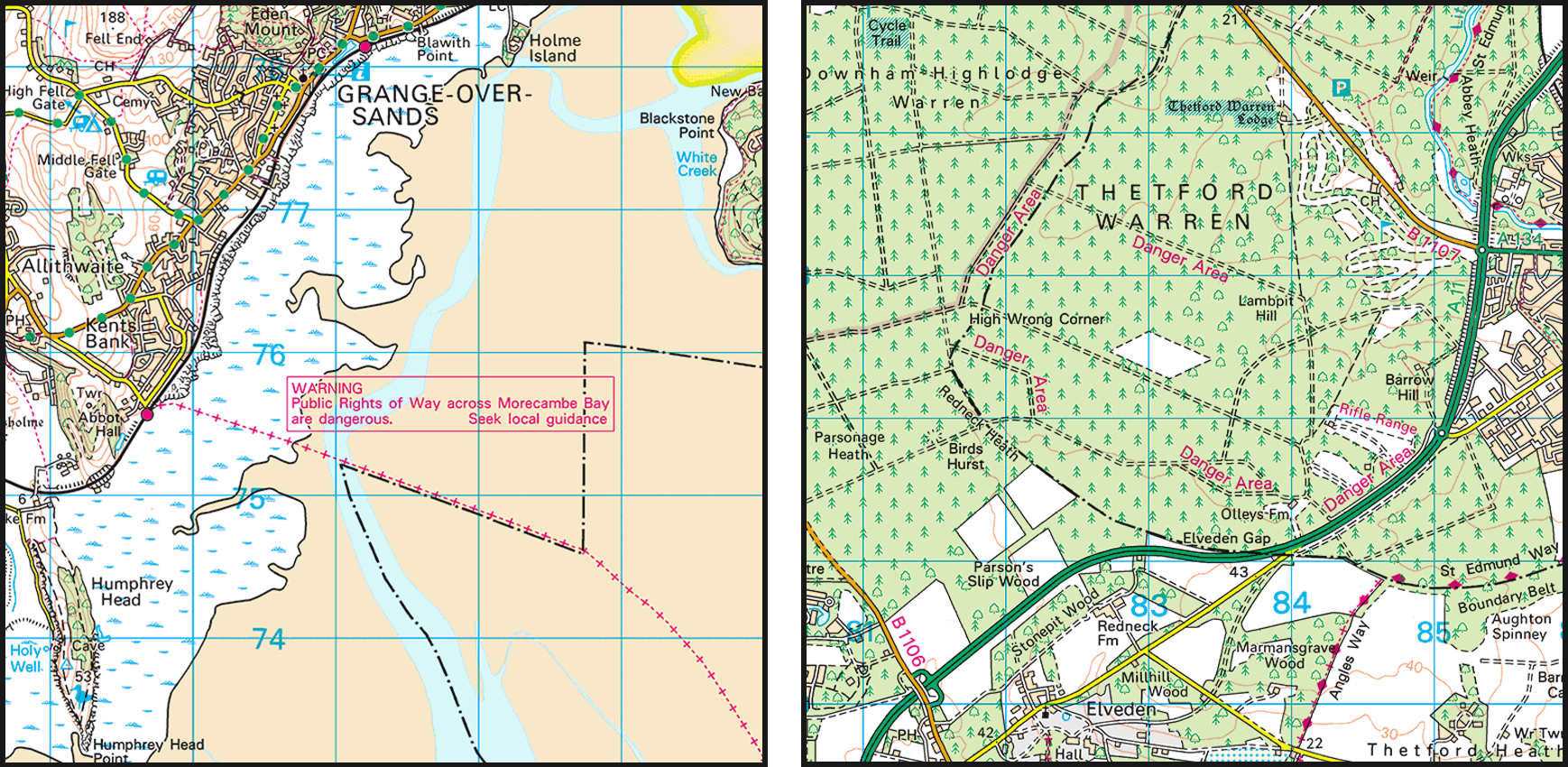

The four maps below show differing scales. Clockwise from top left, the first map extract is at 1:250,000 scale. Maps of this scale typically showing roads but few other features and therefore are designed primarily for drivers. The second map is at 1:50,000 scale, it shows roads alongside some other features and is targeted to cyclists and holidaymakers. The third map (bottom, right-hand side) is at 1:1,250 scale. Such maps can only depict a small area and are typical sought out by those in the building and construction trade. The final map extract is at 1:25,000 scale. At this scale most paths and individual buildings are illustrated and there’s enough details for walkers (be it ramblers or hikers) to plot roots.

All maps are reduced (scaled down) versions of the real world. Scale is therefore represented as a ratio of the map distance to the ground distance. For example, a scale of 1:100 means that one unit on the map represents 100 of the same units on the ground.

Let’s say a road is 10,000cm long (100m) and you want to represent the same road as 10cm on the map, the scale can be calculated by dividing the real-world distance by the map distance. In this case giving 1,000. The scale is therefore 1:1,000 with 1cm on the map representing 1,000cm on the ground.

So, a map with a 1: 50 000 scale will give a bigger, less detailed picture than say a map with a 1: 25 000 scale (which gives a more detailed picture of a smaller area).

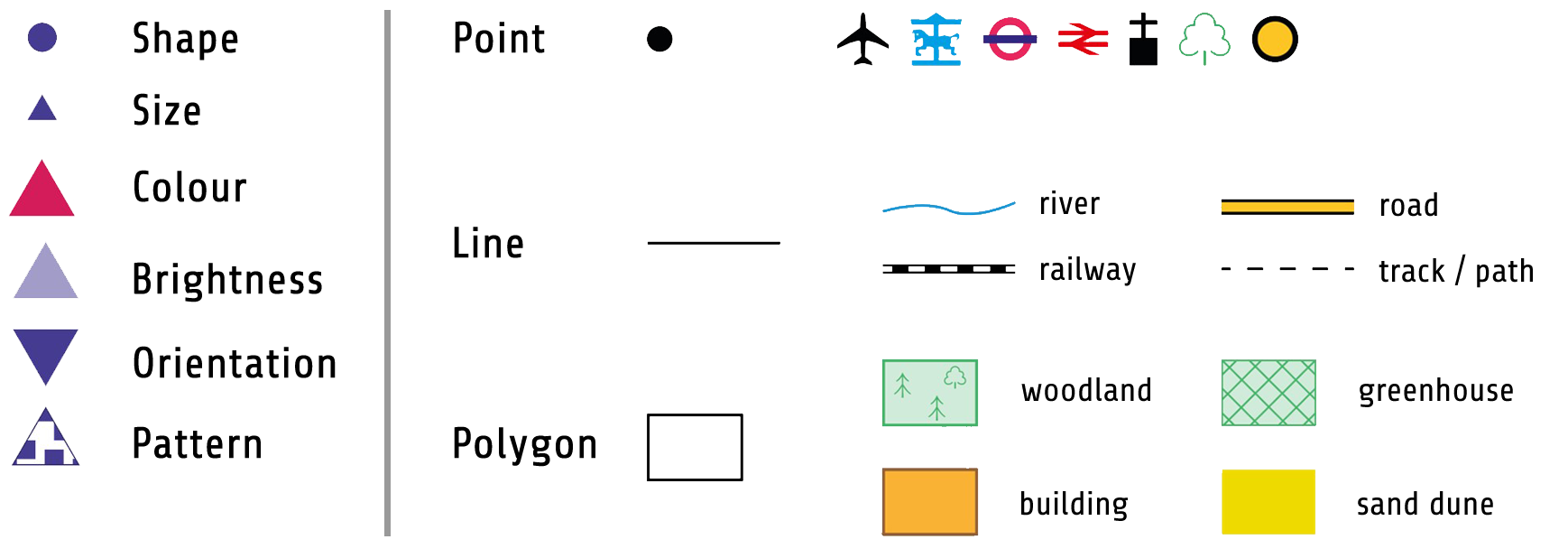

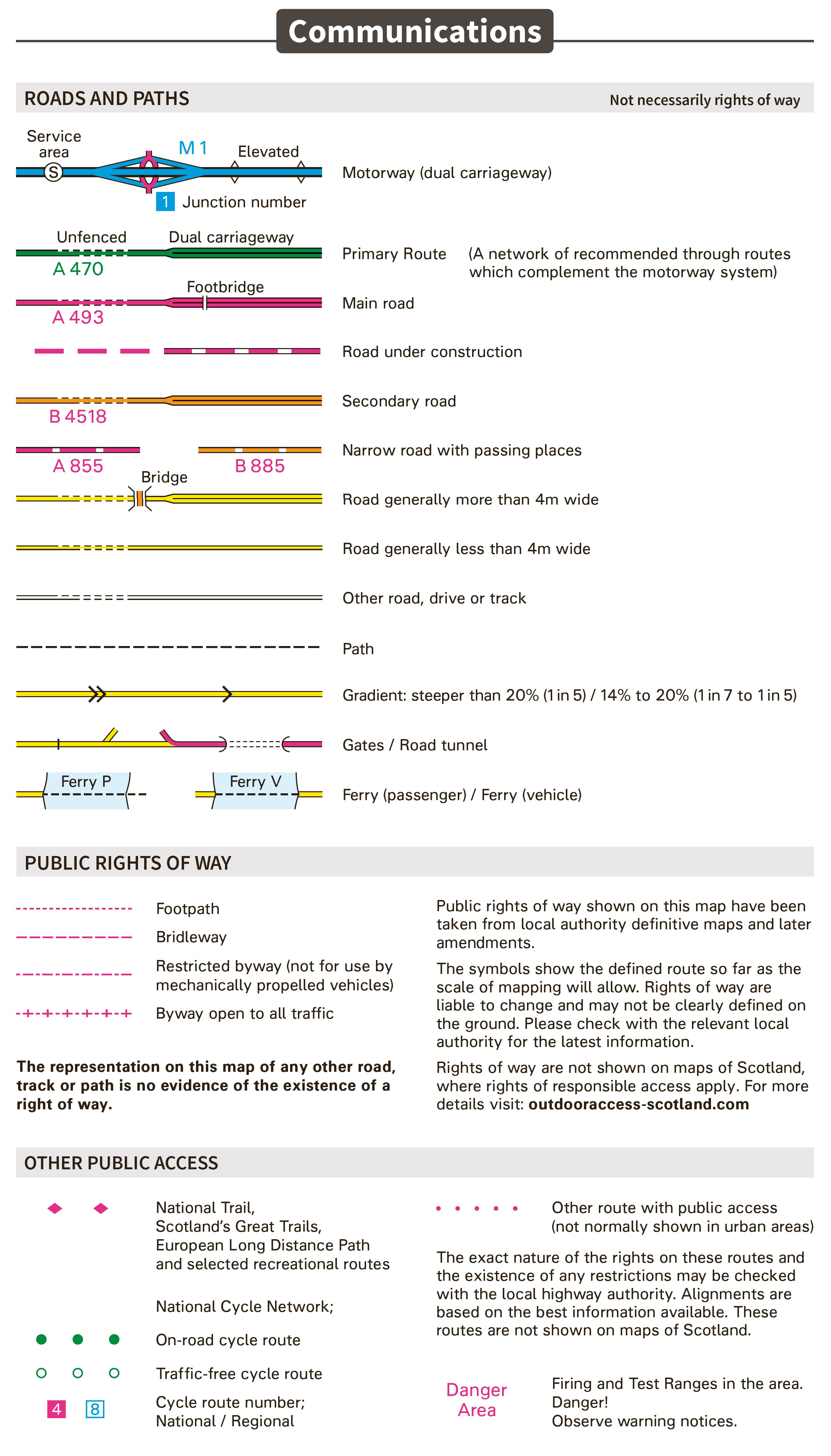

Map symbols &c.

Maps do not show everything in the real world, because they’d be cluttered, confusing or in fact aerial, bird’s eye photographs. Therefore, any given map will highlight (and often symbolise) certain features dependent on (1) its purpose and (2) its intended audience.

OS map legend 1: 25 000 scale →

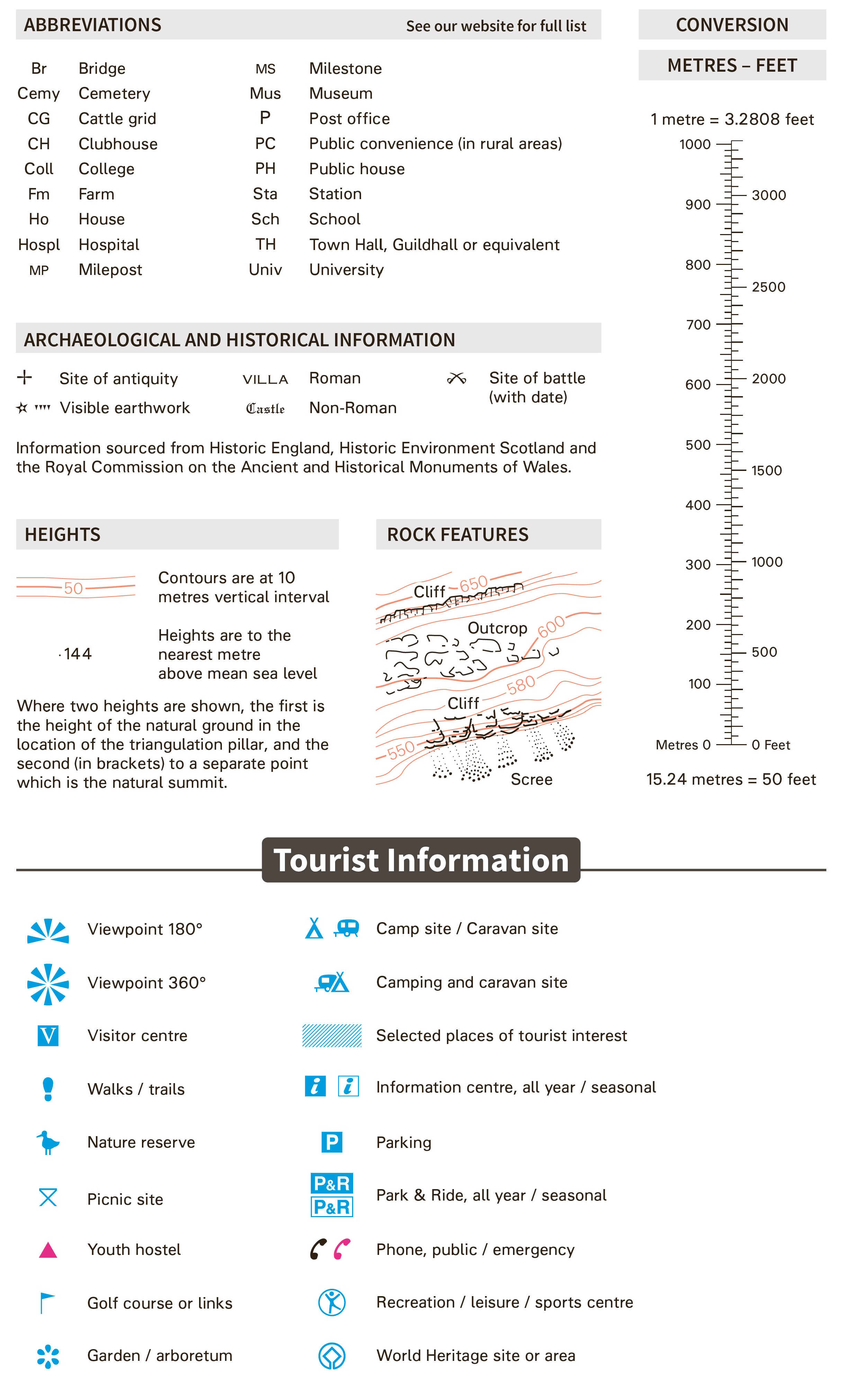

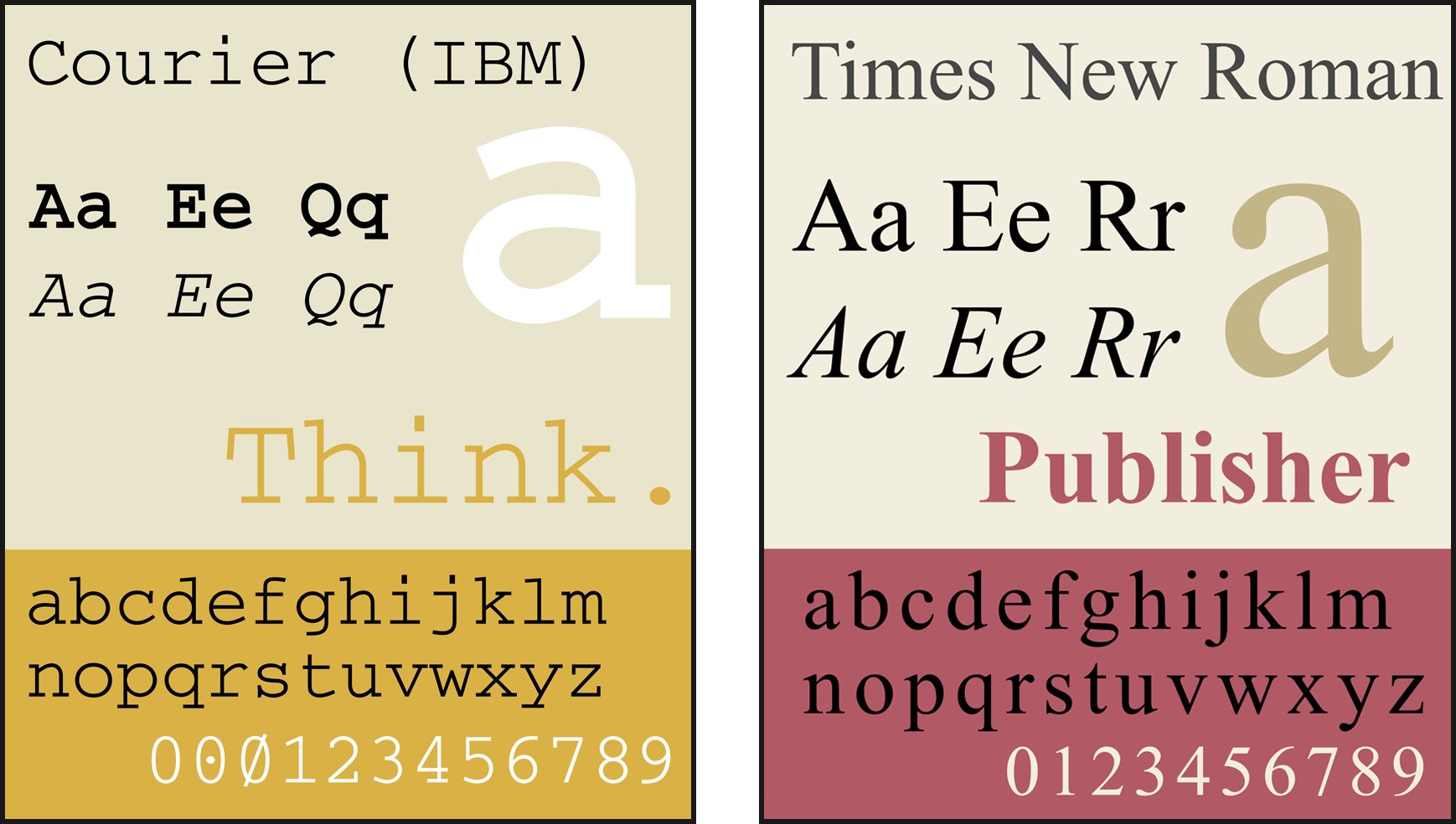

Map typefaces

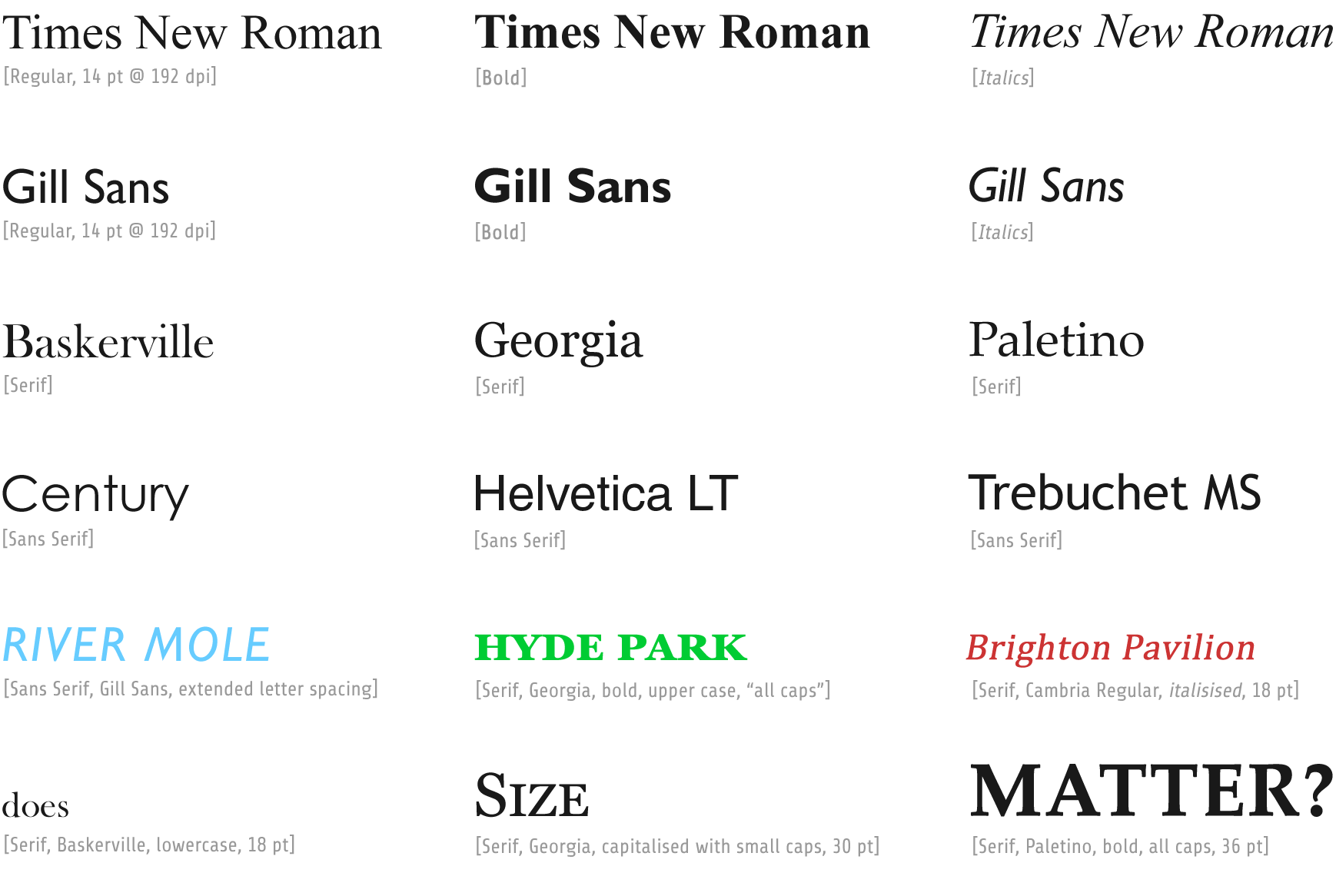

Text in the form of a label, if used effectively, can add meaning to a map and help users understand what they are looking at. On the other hand, poor use of text can make the map appear cluttered and difficult to interpret.

There are many elements of text which can be altered. The first is the typeface (or font). A rule of thumb is to adopt commonly used fonts which are clear and easy to read. A further rule is to limit the number of different fonts used upon a map.

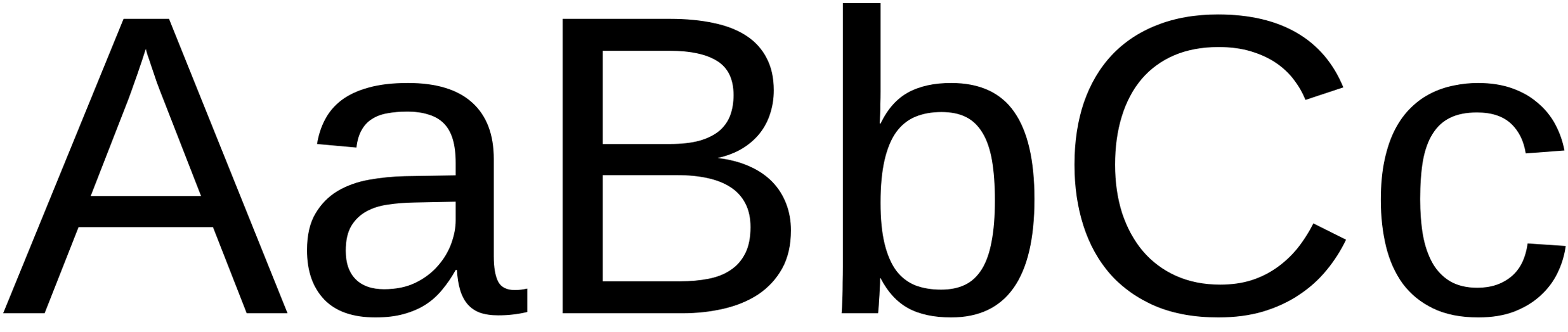

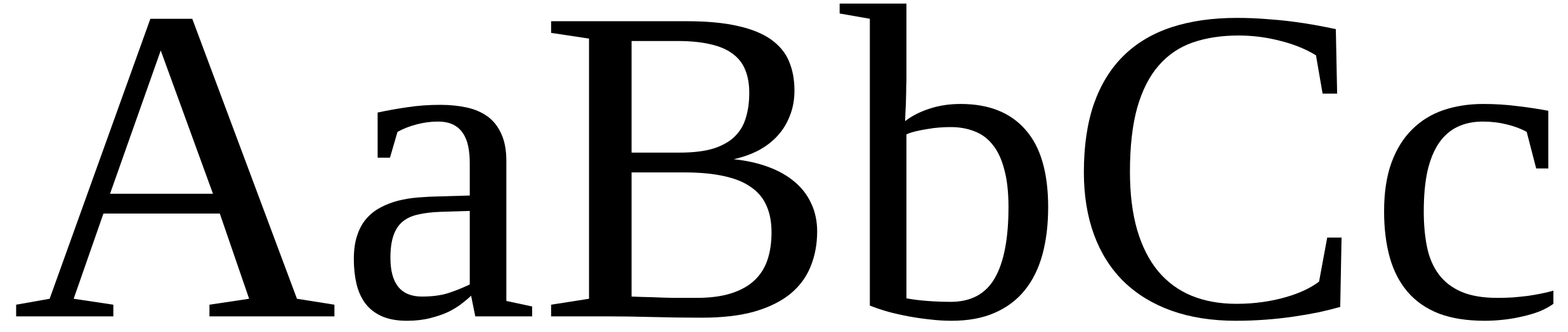

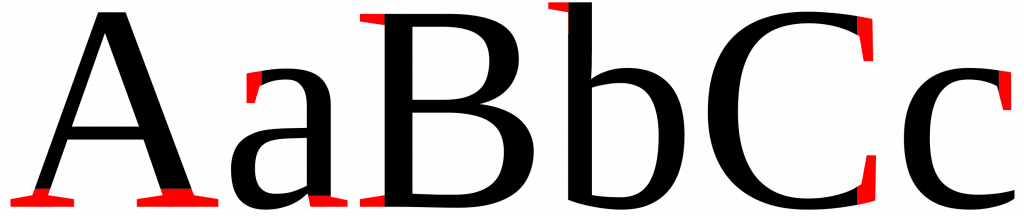

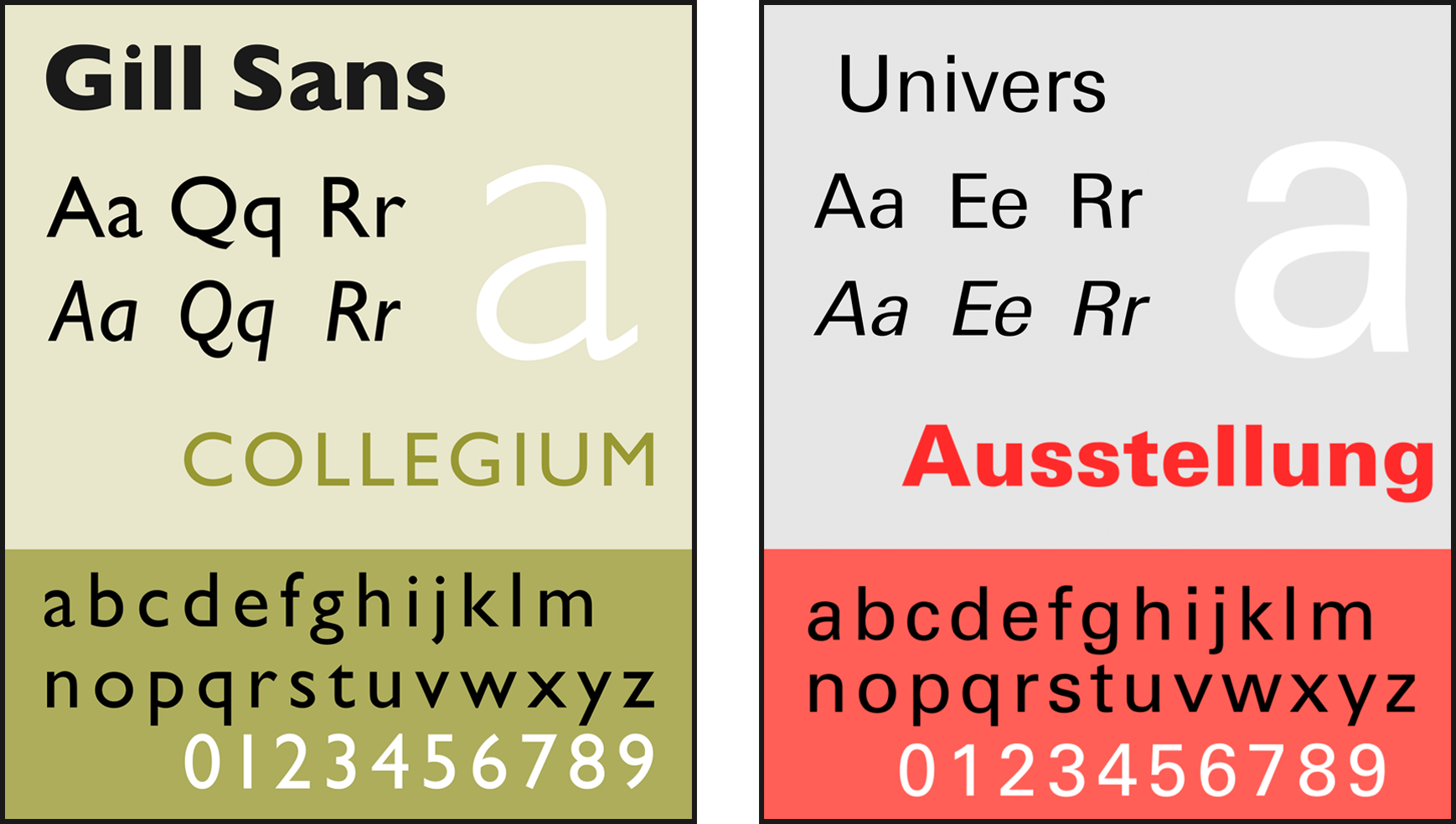

The classic duet

Typeface choice begins with deciding between a serif (more decorative) or a sans-serif (less decorative) font. In typography and lettering, a sans-serif—a.k.a., sans serif; gothic; sans—letterform (font) is one that does not have extending features called “serifs” at the end of strokes.18

Sans-serif & Serif

Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces. They are often used to convey simplicity and modernity or minimalism. For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into several groups: § Grotesque and § Neo-grotesque, § Geometric and § Humanist.

Serif typefaces are commonly used for natural features whilst sans-serif typefaces are often used for manmade/human features. As such, text can be used to differentiate between feature classes.

Other typeface choices include, size, weight, case, spacing and colour. These distinctions can also aid the interpretation of map features.

Most names on OS Landranger (1:50,000; 50K) scale maps use the Univers typeface, most names on OS Explorer (1:25,000; 25K) scale maps use the Gill Sans typeface.

As seen on OS maps:

Placenames & land features

In the case with OS maps, towns are in Univers capitals, size increasing with population; village names and parts of towns have lower case. For natural features type size increases with extent, some are in Gill Sans.

SE3332 LEEDS 22point capitals

SK3635 DERBY 18 point capitals

SJ7194 IRLAM 12 point

NT5347 LAUDER 12 point, a former Royal Burgh with a population around 1800. Even small towns are in capitals.

SJ9283 Poynton 10 point with lower case, population 2001 around 14,000 but a village when map was laid out

SO9337 Westmancote, 8 point

SO9335 Kinsham, 6 point

Some 6 point and 8 point words are in a different typeface, note curly tail on Q in the next three examples. This typeface also has a hooked tail on the lower-case letter L, see Quixhill in third example:

NN8122 curly Quoig

SM9637 curly Quay

SK1041 curly Q, hooked small L

District & parish names

SP0398. On 50K administrative district name is in italic capitals. In this example the placename is adjacent in 18 point capitals. On 25K, district name is shown in grey capitals. On 25K Civil Parish names (in England) are shown in grey capitals, stroke width of letters less than that for district name.

Road numbers & services

Most road numbers and service area names are the same colour as the road, but brown B-roads have red numbers (example see SO9335 Kinsham above).

Names run along features & routes

SO7642 shows the HILLS of MALVERN HILLS along the crest

SP0633 shows Cotswold Way along the path

Large features

On 50K names of a large feature like a peninsula, island or range of hills is spread out along the feature.

NR6921 Letter K of KINTYRE, the rest is spread for 40 km along the peninsula. The image below is a photograph of the strip of Landranger map 68 South Kintyre and Campbeltown showing the KINT of Kintyre spread out, the rest in the margin of the map.

On 25K a large feature name is compact and generally on a horizontal line rather than along the feature

Blue lettering, for water features

SX9355, sea area, blue letters with lower case

SU4807 wide watercourse, blue letters in capitals

Blue letters are also used for inland lakes, ocean bays and channels, type size varying with extent of feature. As for 6pt and 8pt place and feature names, some watercourse names are in a typeface with a curly tail Q, here in Quarters,

TL9911

Red lettering, for dangerous areas

Army training grounds and coastal footpaths which can be dangerous through height, tide or mud may have red warning notes, e.g., Morecambe Bay.

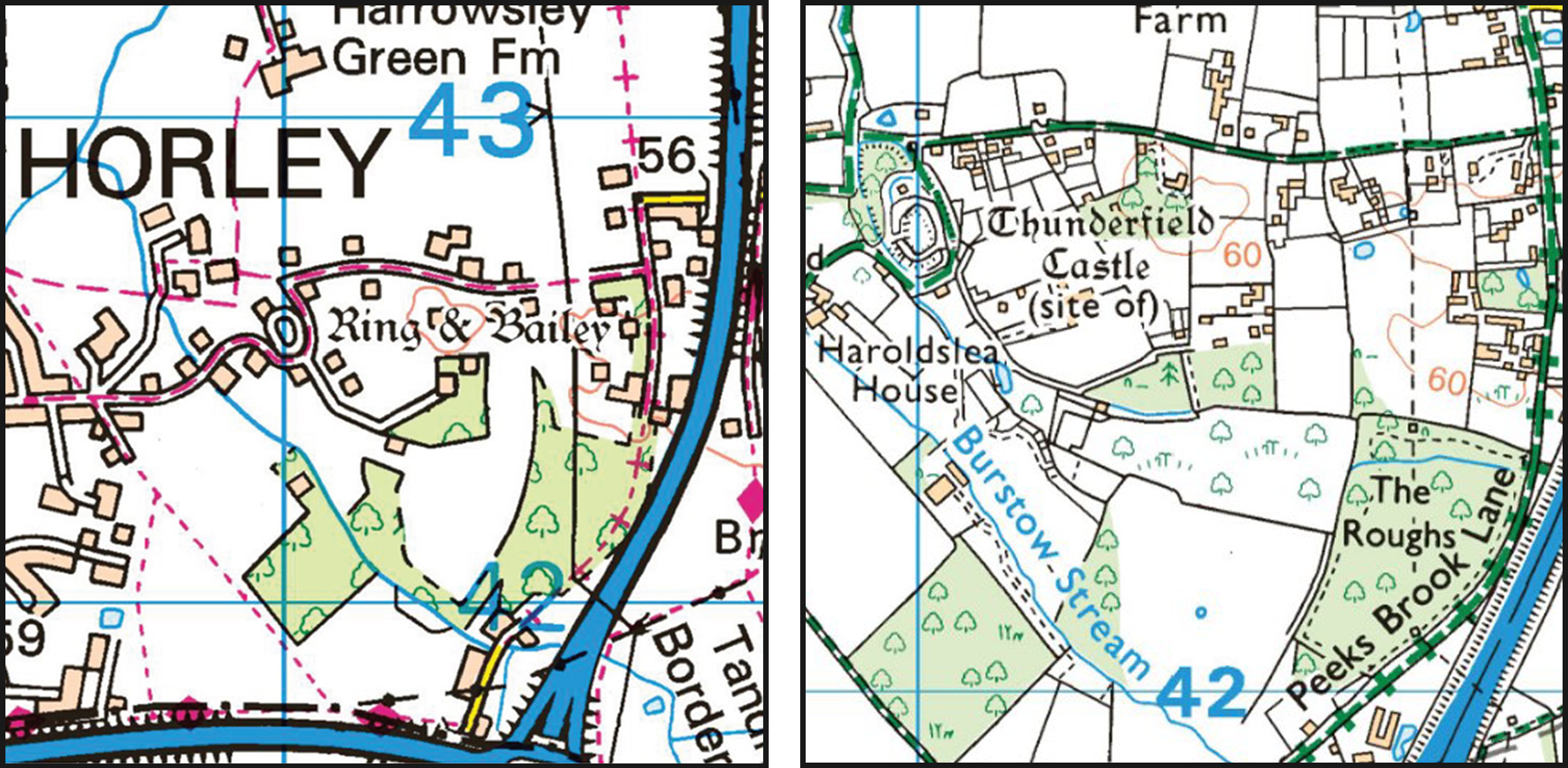

Antiquities

Gothic typeface on an OS map depict pre- and post-Roman antiquities. Below we see “Ring & Bailey,” we also see “Thunderfield Castle;” both are in a classic gothic font.

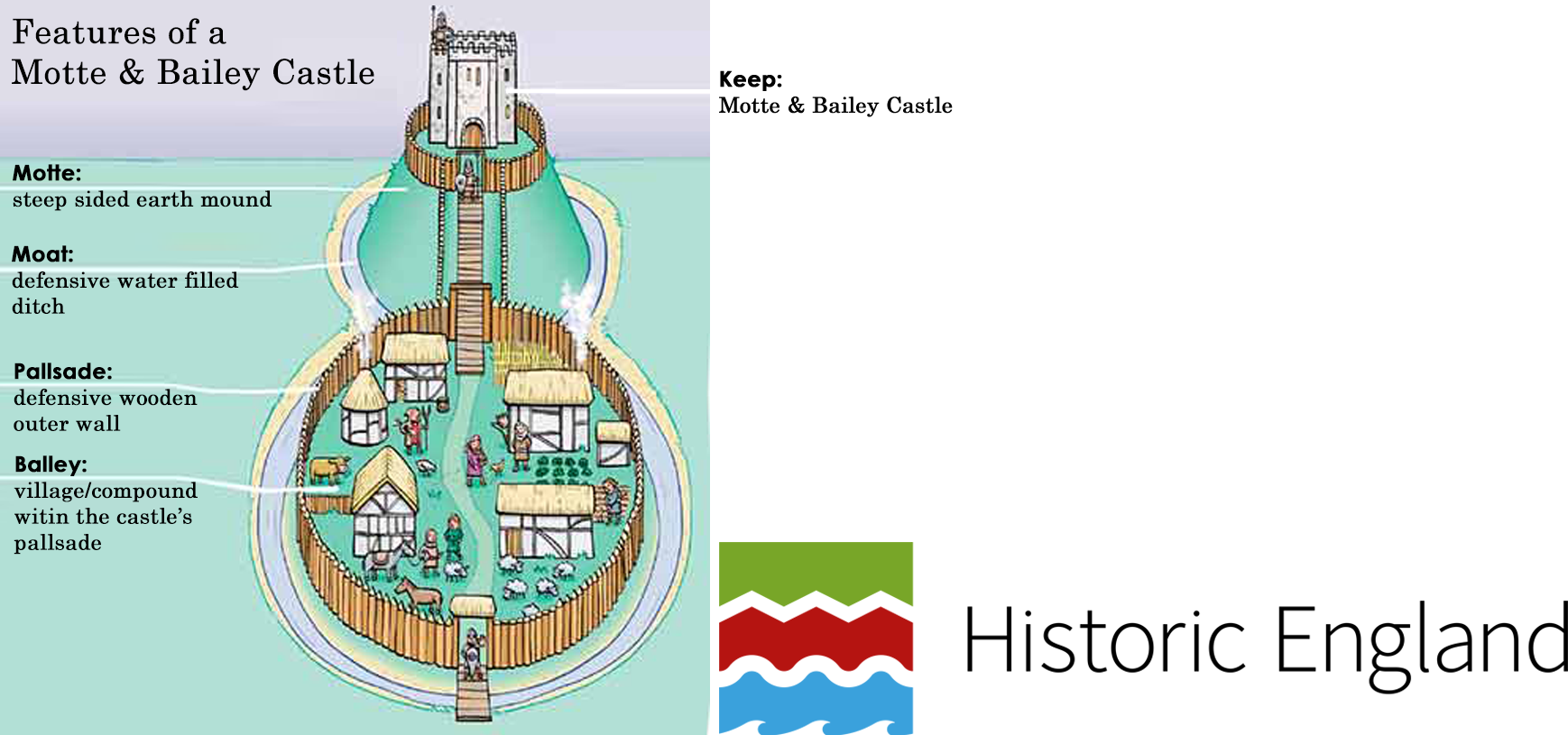

Motte and Bailey castles comprised a strong wooden, or sometimes stone, structure known as a Keep – occupied by the military force’s senior figures – built onto a raised Motte, an often steep-sided, frequently artificial, conically shaped earthen mound. An encircling wooden palisade was often added to increase security. A moat, too, was sometimes built around the whole complex giving those within a further layer of protection.

The Bailey was an adjacent embanked, often fenced enclosure within which were located living quarters for the troops, storage space for military equipment and foodstuffs, resting places for horses and other livestock, and space for the further necessities associated with early post-Conquest warfare. The Bailey was usually on level ground and was also often protected by a wooden palisade, and external ditch.

Ringwork castles are characterised by the absence of a motte. The keep, if indeed there was one, was sited within a usually oval or circular-shaped ringwork, sometimes referred to as an Inner Bailey. This area was enclosed by an earthen rampart sometimes topped by a timber palisade, and protected by a substantial ditch.

According to Historic England, ringworks are rare nationally with only 200 recorded examples; less than 60 of them have baileys.

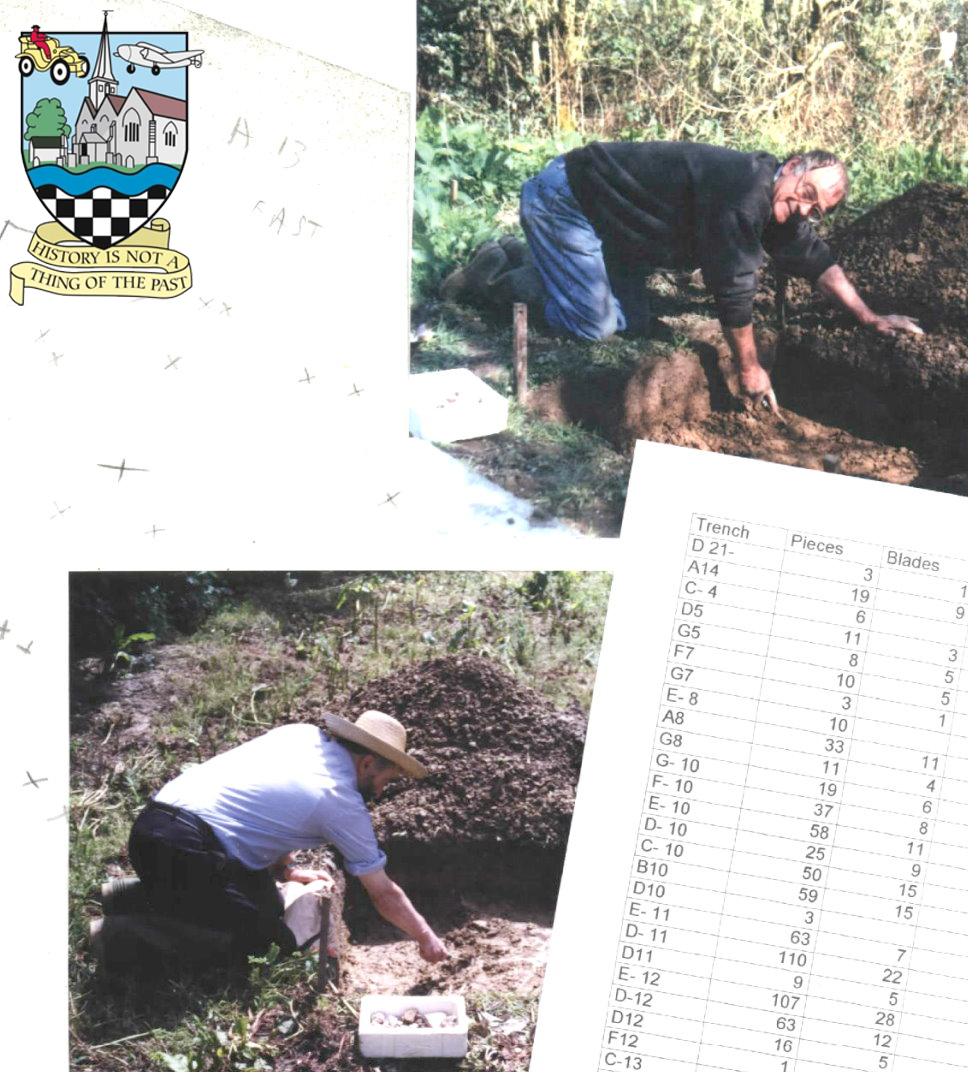

Digging for pre-history

Footnotes

- Horley Parish formed part of the former Abbey of Chertsey’s Sutton estate. The manor of SUTTON or SUTTON ABBAS formed part of the lands included in the alleged gift to Chertsey Abbey of 727 (for which see Beddington) as well as in those of Athelstan and Edgar confirming the original donation. In 1086 the abbey of St. Peter of Chertsey held land at Sutton assessed at 30 hides in the time of King Edward, and then at 8½ hides (a hide was an English unit of land measurement originally intended to represent the amount of land sufficient to support a household. It was traditionally taken to be 120 acres [49 hectares], but was more often considered a measure of value and tax assessment, including obligations for food-rent [feorm], maintenance and repair of bridges and fortifications, manpower for the army [fyrd], and eventually, the land tax [geld]). Appertaining to the manor was a separate holding in the Weald at Thunderfield near Horley. In the Domesday Survey two churches are mentioned on the manor (Sutton Advowson [Sutton/Chertsey Abbey]), worth £20 before the 1066 Norman Conquest, and in 1086, £15. The history of one of these churches is very obscure and a possible supposition is that it was at Horley in the Weald (unmentioned in Domesday), which belonged to Chertsey, and close to which were the thirty mansae (noun, archaic : the dwelling of a householder; the residence of a minister; a large imposing residence) at Thunresfelda (Thunderfield) mentioned in Athelstan’s and Edgar’s charters as attached to this manor. Thunderfield Common was partly in Horley, partly in Horne, but close to Horley Church, the advowson of which belonged to Chertsey from a date unknown. See: “SUTTON,” https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/surrey/vol4/pp243-246 for source references. ↩︎

- What follows is an abridged form of the article, “Disgust as six acres of woodland hacked down in Horley,” as posted by Jenny Seymour to SurreyLive on the 9th of December, 2020. [strapline: “Police and the Forestry Commission are investigating after six acres of woodland was cut down — to the horror of residents] The trees were hacked down on private land that was earmarked five years ago as the home for a vast business park. No planning application has yet been submitted for the scheme in Horley—on a triangle of green land between the town and Gatwick Airport—which has not moved beyond the early planning stages. Sara Marchant, who lives close to the site off Balcombe Road, said residents were heartbroken at the “devastation”. Marchant pointed out that this “woodland was home to so many different species [and that] there were bats there and barn owls too.” ↩︎

- The crest of Horley’s freemason society depicts Harold II the Saxon King holding in his left hand a chequered shield, as representing the floor of Masonic lodges. This chequered pattern may also have some connection to the ‘Fitzwarren’ family’s coat of arms, who were lords of the manor of Horley for many years. According to this group of freemasons, “various names were suggested for the lodge but ‘Haroldslea’ was finally decided upon. This was apparently the old name for Horley, where the lodge used to meet. As far as can be discovered ‘Haroldslea’ is derived from the earlier name ‘Harrowley’ which is in turn derived from ‘Herewoldsle’ which is the earliest known name on record that can be found around the time of the Anglo-Saxon period.” ↩︎

- Janaway, J (1991). Ghosts of Surrey. Newbury, England: Countryside Books. ↩︎

- “Thunderfield & Haroldslea” by Peter Charles Cox Esq. — To the south-east side of Horley there is an area of about 680 acres stretching from a point north-east of Langshott Manor to the Gatwick link road, and a point about a quarter mile east of Balcombe Road across the M23 motorway. This area was known for many years as the Manor of Haroldslea. From early times it was a detached part of the Parish of Horne, until 1894 when it was transferred to Horley. Within this area there is an unusual moat. Basically it is two concentric moats. Within the inner moat there is a main central island and a smaller island. The site is a listed “National Monument” therefore it is not possible to excavate the site. Back in 1936 a small hole was dug and revealed that iron had been smelted there and pottery dated from around the 13th to 15th centuries was also found. Such pottery fragments are fairly common in the surrounding area. What is known is that there was a manor court held in Haroldslea in the early 13th century. Documents in the British Library (ADD Charters 5932 & 7599) refer to the people of Horne having to pay their rents into the court of “Herewoldeslea” There are no known old legal references to a castle in the area, indeed the first reference to Thunderfield Castle was an 18th century historian (Aubrey) who named the moat as Thunderfield Castle. During the same period several maps refer to Horne Castle. Later maps followed the tradition that the site was of Thunderfield Castle. In view of the fact that there is no legal reference known of a castle in the area, but that there is evidence of a manor court, we are left to suggest that the site was of a timber framed manor house. Whether or not there was ever any kind of fortification on the site is pure speculation, as nothing has ever been found, except some burnt timbers in the moat which could have come from a house or barn. Thunderfield was a common or heath which covered most of what is now Horley from Horley Row and Ladbroke Road right down to just to the north of Tinsley Green, but included only just a narrow strip of Haroldslea and a bit of Burstow near Peeks Brook Lane. Indeed, it is quite probable that Thunderfield Common originally included a much larger area of land. It is named in Anglo Saxon documents dating back to 880. Thunderfield Common belonged to Chertsey Abbey, and was described in their records as 3,000 acres in [the manor] of Sutton with a den for pigs. Some of the Abbey’s documents are believed to be forgeries so nothing is certain. To sum up, Thunderfield refers to an ancient common which was used to graze pigs. The modern town of Horley is built on this common. ↩︎

- See — Ellaby, R. (2010). Horley revisited: reflections on the place-name of a Wealden settlement. Surrey Archaeological Collections, 95, pp. 271–279. ↩︎

- Chertsey Abbey, dedicated to Saint Peter, was a Benedictine monastery located at Chertsey, Surrey (next to the river Thames). It was founded in 666 CE by Saint Erkenwald who also happened to be the Bishop of London at that time. St. Erkenwald and his abbey was ‘given’ a large chunk of what is today Surrey by King Frithuwald. In the 9th century it was sacked by the Danes and reestablished from Abingdon Abbey by King Edgar of England in 964. The abbey was dissolved by the commissioners of King Henry VIII in 1537; Horley and its environs was given (or sold at a discount) to member’s of that King’s court. ↩︎

- As stated by the Horley Local History Society, “After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, Horley Manor passed to Henry VIII who gave or sold it to various people until 1602, when it became the property of Christ’s Hospital in London. A map of its purchase was produced in that year, the original of which is held today by the Guildhall Library in the City of London.” ↩︎

- ibid. Ellaby (2010). ↩︎

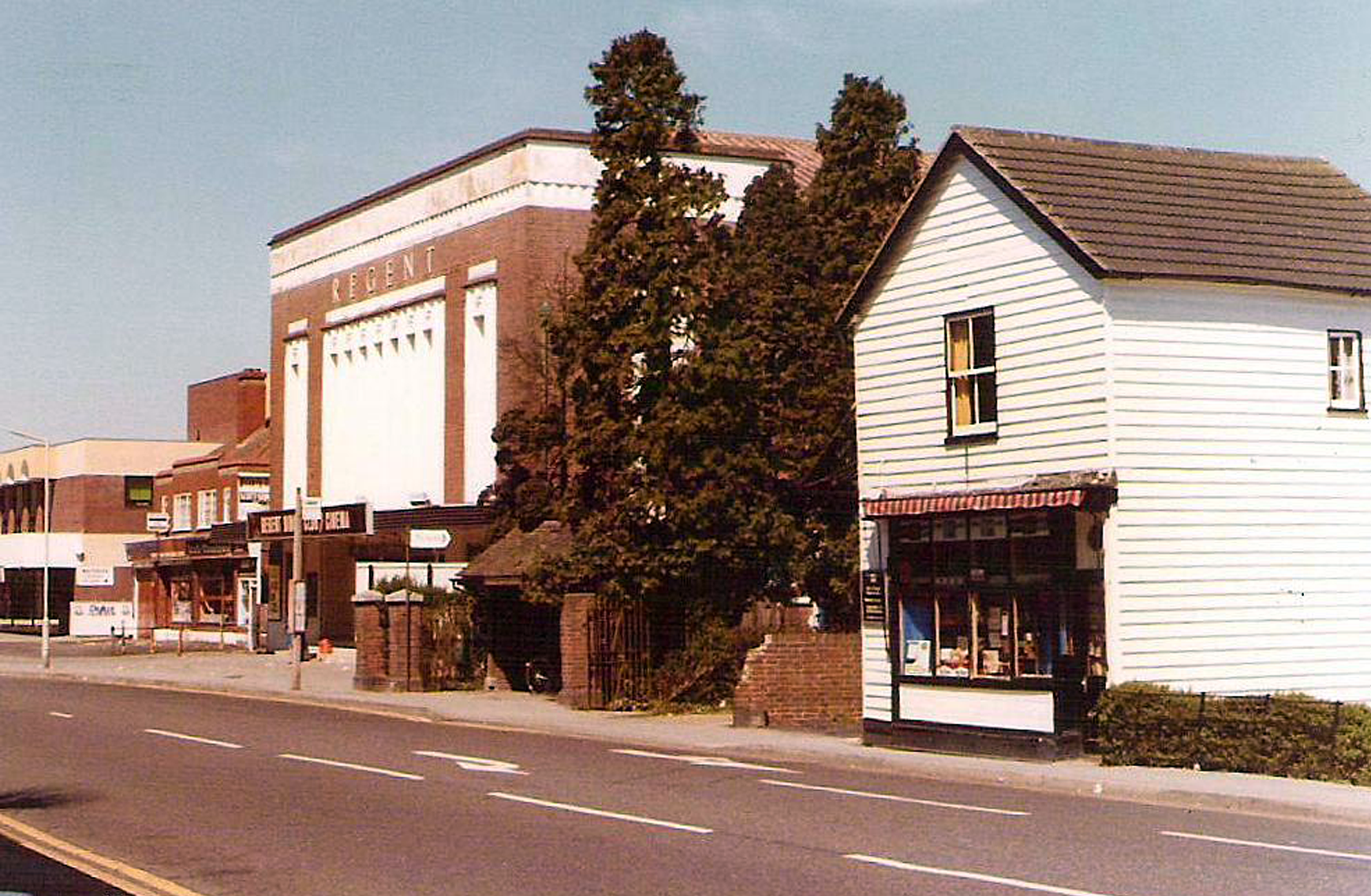

- Horley’s Regent Cinema was built by the Shipman & King chain, and opened on 14th March, 1935. It had a 30 feet wide proscenium and was upgraded with CinemaScope in 1954. In October 1975, it was sold to the Myles Byrne chain. It closed down and was demolished in 1981. ↩︎

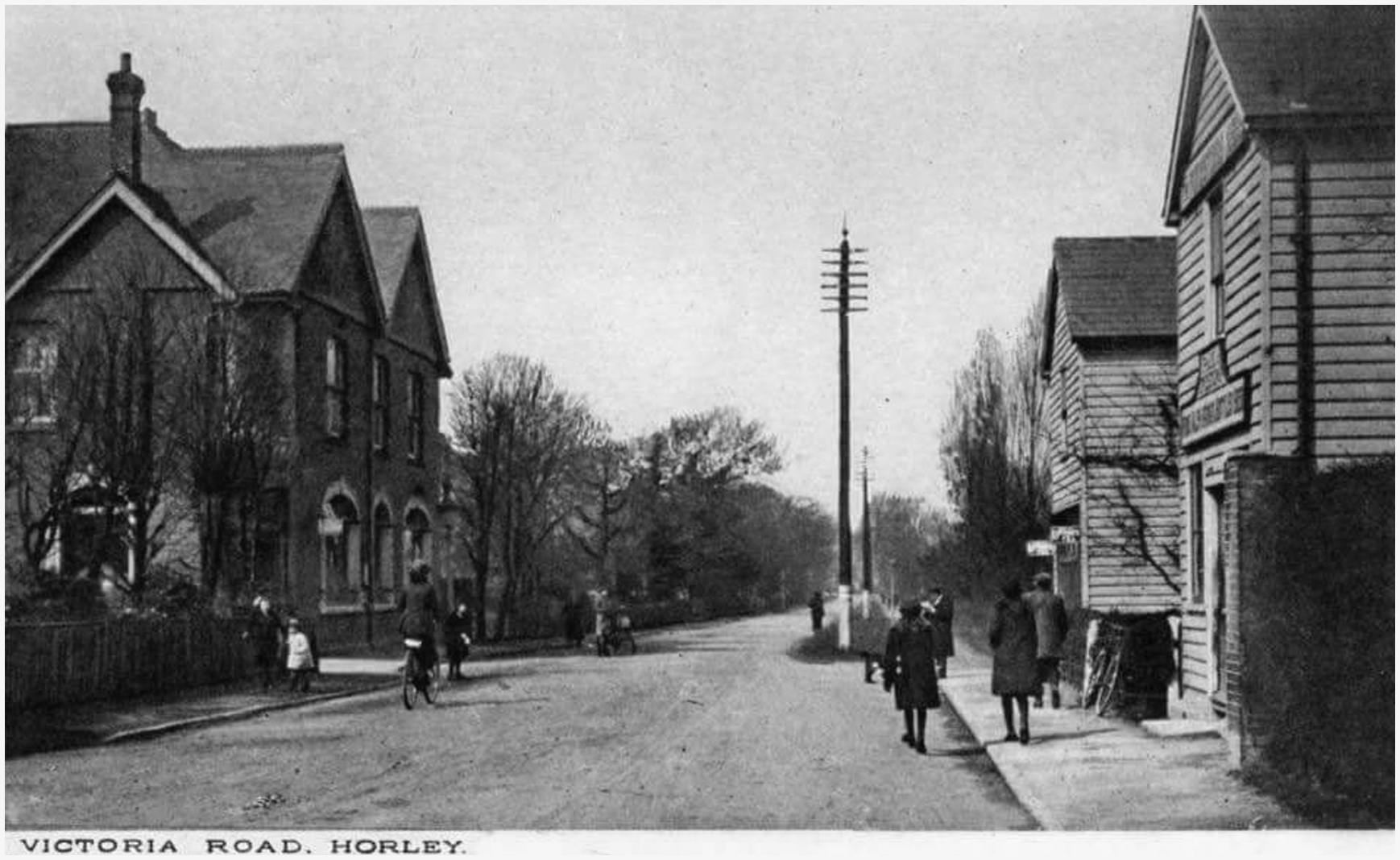

- Horley’s former post office was built in 1905 to the designs of architect T.W. Parrish and extended probably in the 1930s in the preferred “Post Office” Georgian style. ↩︎

- The relocating of the station by a few hundred feet coincided with the quadrupling of the railway line by the London Brighton and South Coast Railway Company. ↩︎

- The initial Horley railway station was on a larger scale than other intermediate stations on the Brighton to London line because, being situated almost midway between London and Brighton. Thus, Horley was chosen for the erection of the London and Brighton Railway carriage sheds and repair workshops (they were though moved to Brighton some 50 years later). Railway sidings at Horley were used for storing withdrawn locomotives and those awaiting repair until the First World War. ↩︎

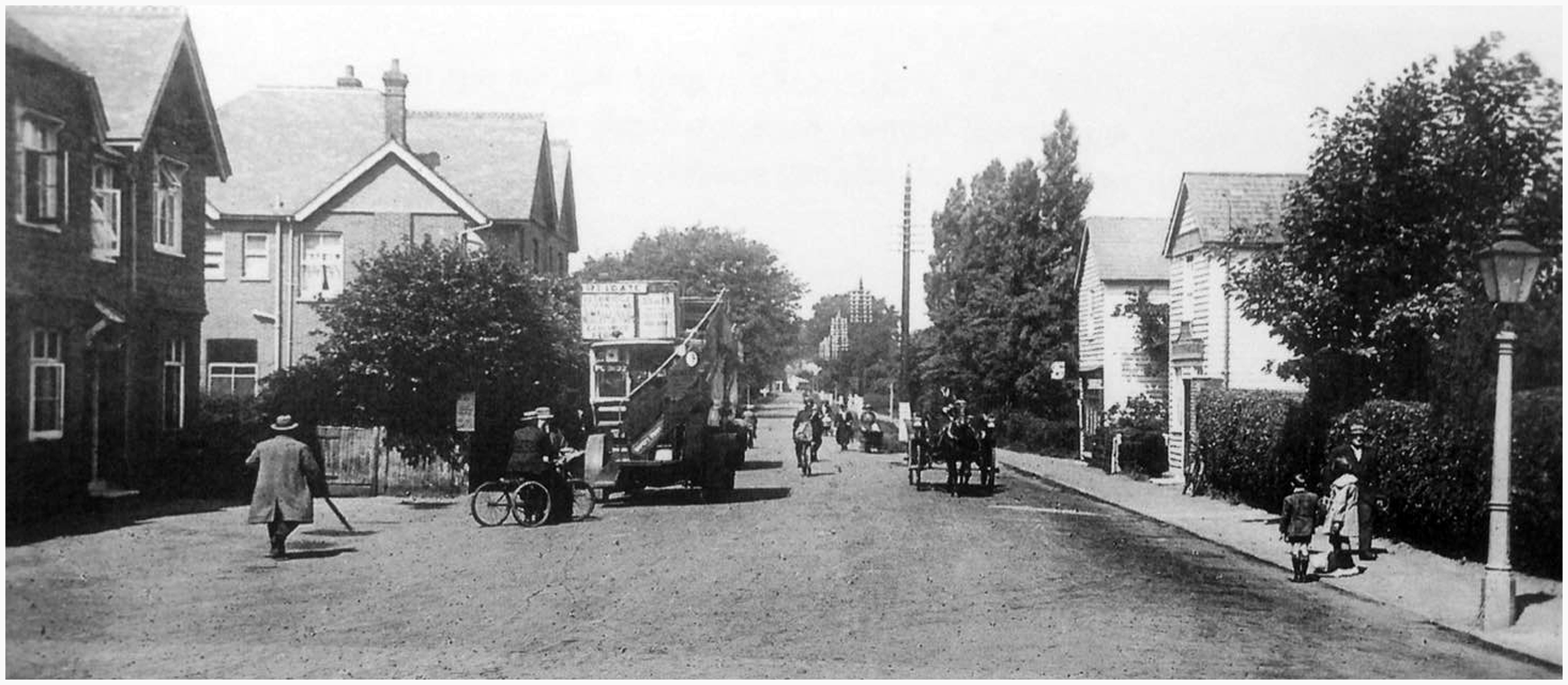

- The quadrupling of the railway in 1905 led to the crossing being severed and replaced by a subway, with this footbridge being added later. At the same time the station was moved around 300 metres to the south, with a station building on a new Victoria Road overbridge, this too had previously crossed the railway at a level crossing. ↩︎

- According to Forgotten Spaces (https://youtu.be/KYpj2dYdvrM) this site closed down on the 6th of December, 2013. The plan was to turn it into a four star hotel and create up to 60 jobs, however the site remains closed and in worse repair than before, leading locals to wonder what is happening with it (this was written in 2020, it is now a pub called “Halt & Pull”). The Chequers dates to 1745. Back then, coaches and horses would stop here on their way to London up from the south coast. ↩︎

- Another entry for the record, Courier is a monospaced slab serif typeface. It was created by IBM in the mid-1950s, and was designed by Howard “Bud” Kettler (1919–1999). The Courier name and typeface concept are in the public domain and versions of it are installed on most desktop computers. ↩︎

- For the record, Times New Roman is a serif typeface that was commissioned by the British newspaper, The Times in 1931. It was conceived by Stanley Morison, the artistic adviser to the British branch of the printing equipment company Monotype, in collaboration with Victor Lardent, a lettering artist in paper’s advertising department. It has become one of the most popular typefaces of all time. ↩︎

- In typography, a serif is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or “font family” making use of serifs is called a serif typeface, and a typeface that does not include them is sans-serif. Some typography sources refer to serif typefaces as “roman”. Serifs originated from the first official Greek writings on stone and in Latin alphabet with inscriptional lettering (words carved into stone in Roman antiquity). The explanation proposed by Edward Catich in his 1968 book, The Origin of the Serif, is now widely accepted: the Roman letter outlines were first painted onto stone, and the stone carvers followed the brush marks, which flared at flared at stroke ends and corners, creating serifs. However, another theory suggests that serifs were devised to neaten the ends of lines as they were chiselled into stone. ↩︎

- Arial (also called Arial MT) is a sans-serif typeface and set of computer fonts in the neo-grotesque style. Fonts from the Arial family are included with all versions of Microsoft Windows, Apple’s macOS and, many PostScript printers. Each of its characters has the same width as that character in the popular typeface Helvetica; the purpose of this design is to allow a document designed in Helvetica to be displayed and printed with the intended line-breaks and page-breaks without a Helvetica license. From MS Office 2007, Arial was replaced by Calibri as the default typeface in PowerPoint, Excel, and Outlook. ↩︎

- Cambria is a transitional serif typeface commissioned by Microsoft and distributed with Windows and Office. It is intended as a serif font that is suitable for body text, that is very readable printed small or displayed on a low-resolution screen and has even spacing and proportions. It is part of the ClearType Font Collection (which includes fonts starting with the letter C including, Calibri, Candara, Consolas, Constantia and Corbel). They are crafted to work well with Microsoft’s ClearType text rendering system, a text rendering engine designed to make text clearer to read on LCD monitors. ↩︎

- Gill Sans is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Eric Gill and released by the British branch of Monotype from 1928 onwards. Gill Sans is based on Edward Johnston’s 1916 “Underground Alphabet”, the corporate font of London Underground. As a young artist, Gill had assisted Johnston in its early development stages. ↩︎

- Univers is a large sans-serif typeface family designed by Adrian Frutiger and released by his employer Deberny & Peignot in 1957. Classified as a neo-grotesque sans-serif, one based on the model of nineteenth-century German typefaces such as Akzidenz-Grotesk, it was notable for its availability from the moment of its launch in a comprehensive range of weights and widths. The original marketing for Univers deliberately referenced the periodic table to emphasise its scope. ↩︎